Shopping for new speakers can be daunting. With so many vendors and companies vying for your hard-earned cash, and online forums awash in opinionated anecdotes and sonic mythology, it is very difficult to assess what speakers you should invest in.

You probably have physical limitations on your rental space too. You can't hang any serious acoustic treatment on the walls, you have essential furniture in less than ideal places, and your neighbours have hearing so sensitive you kind of envy them. This makes choosing the correct speaker size critical to hearing more accurately, despite these common drawbacks.

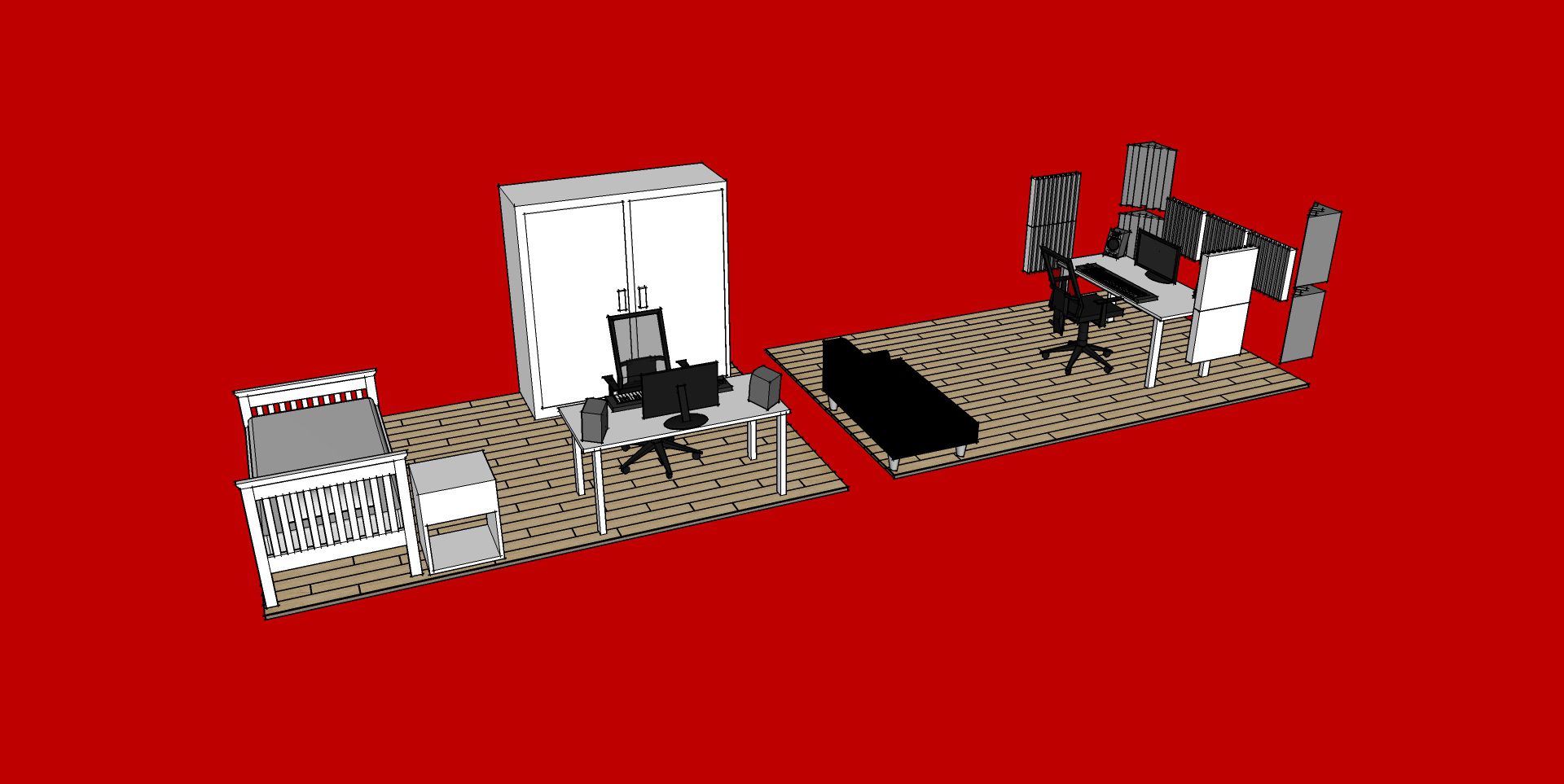

Fig 1: Reality vs. The ideal

Over the course of two articles, I will explain why monitors smaller than 7” are ideal, arguably necessary, for small project studios.

Why Go Small?

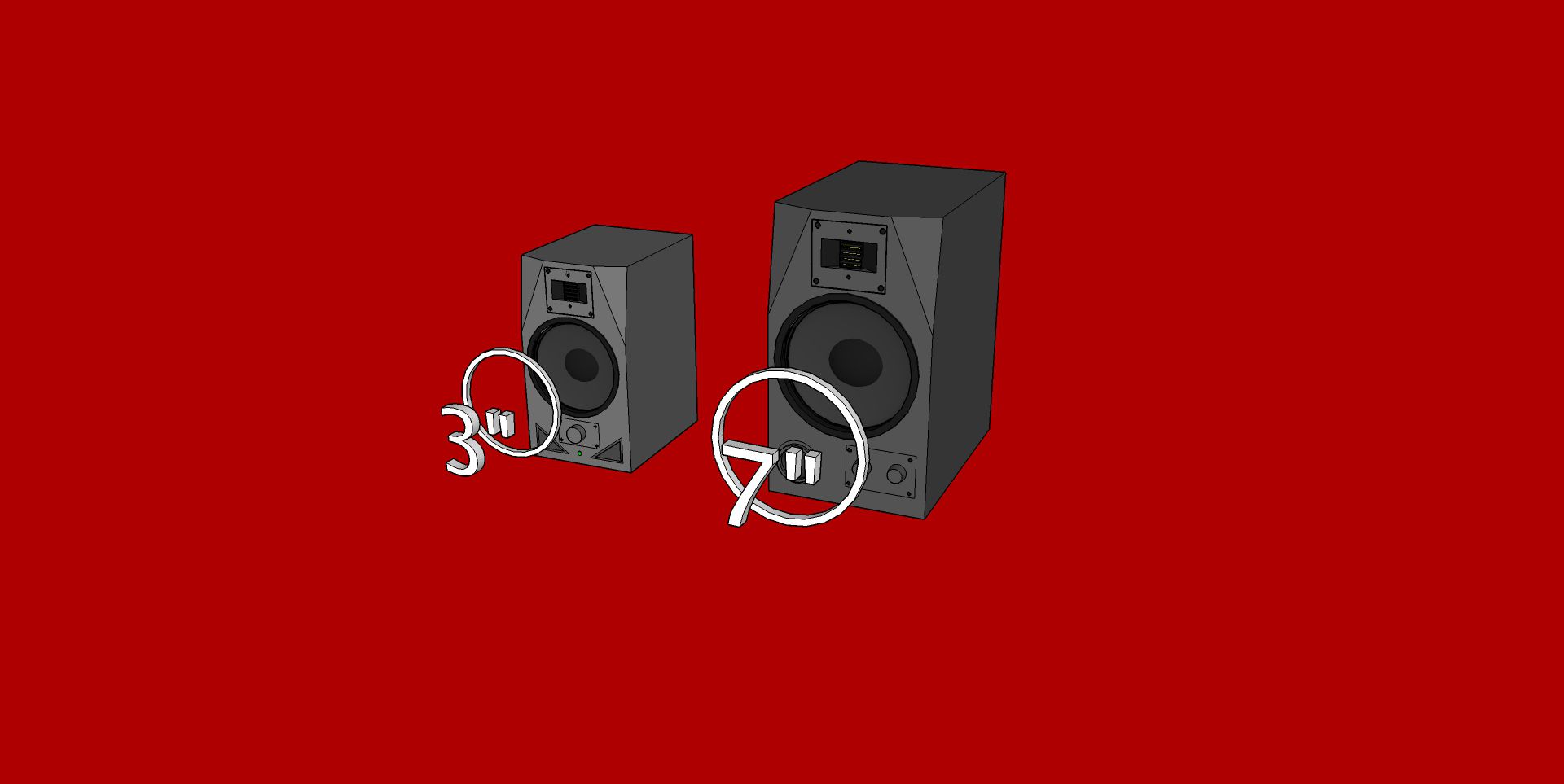

Fig 2: “Small speakers” in this article refer to any monitor with a cone 7” and smaller.

Straight out the gate, here are some of the more obvious selling points on small monitors:

- They're inexpensive. For less than €500 you can buy a pair of 3” speakers that, for the price, outperform their larger counterparts, even in the low end.

- Paying less for smaller, professional monitors, (rather than larger “budget” monitors) might also free up some money for acoustic treatment and/or other gear.

- Smaller speakers take up less physical space, and are easier to place, fitting right onto your desktop.

Okay, that's the obvious stuff, let's dig a bit deeper into the hidden benefits of small speakers in small rooms, and see why bigger isn't necessarily better.

Big speakers are there to impress clients

In most high-end studios the big speakers are primarily used to show off mixes to clients at high dBSPLs. The room is acoustically tuned to these speakers. They are the ones pushing the most amount of pressure into the room and thus need the most controlling. These farfield speakers also need to have a wide sweet spot so that clients, producers and band members can appreciate the music from multiple areas in the control room.

Fig 3: Pink Studios, Belgrade—Soffit mounted Dynaudio Pro M3 with Yamaha NS-10Ms on the bridge of an SSL 6000 E console.

Primary, functional mixing is almost always performed on smaller, near field monitors, with a much narrower sweet spot centered around the mix position of one person, the engineer.

Why?

Small speakers prevent too strong a reverberant field from building up in a room, especially in the low end. Bass frequencies are notoriously difficult to control, even in dedicated, built to order studios, and only the creme de le creme of facilities can boast flat frequency response below 200 Hz.

A nearfield monitor speaker allows an engineer to sit much closer to the sound source at lower SPLs. This means that most of the sound from the driver and tweeter travels directly to the ear, rather than reflecting off walls and ceilings, and picking up coloration and reverberation from the room on the way.

It's quite simple; speaker size should be proportional to room size.

Defining a small room

So, what constitutes a small room? Most audio specialists consider the following a rough guide to room sizes:

• Small room: Anything under 42 m^3 (1,500 ft^3)

• Medium room: Anything from 42m^3 to 85m^3 (1,500 ft^3 to 3,000 ft^3)

• Large room: Anything over 85m^3 (3,000 ft^3)

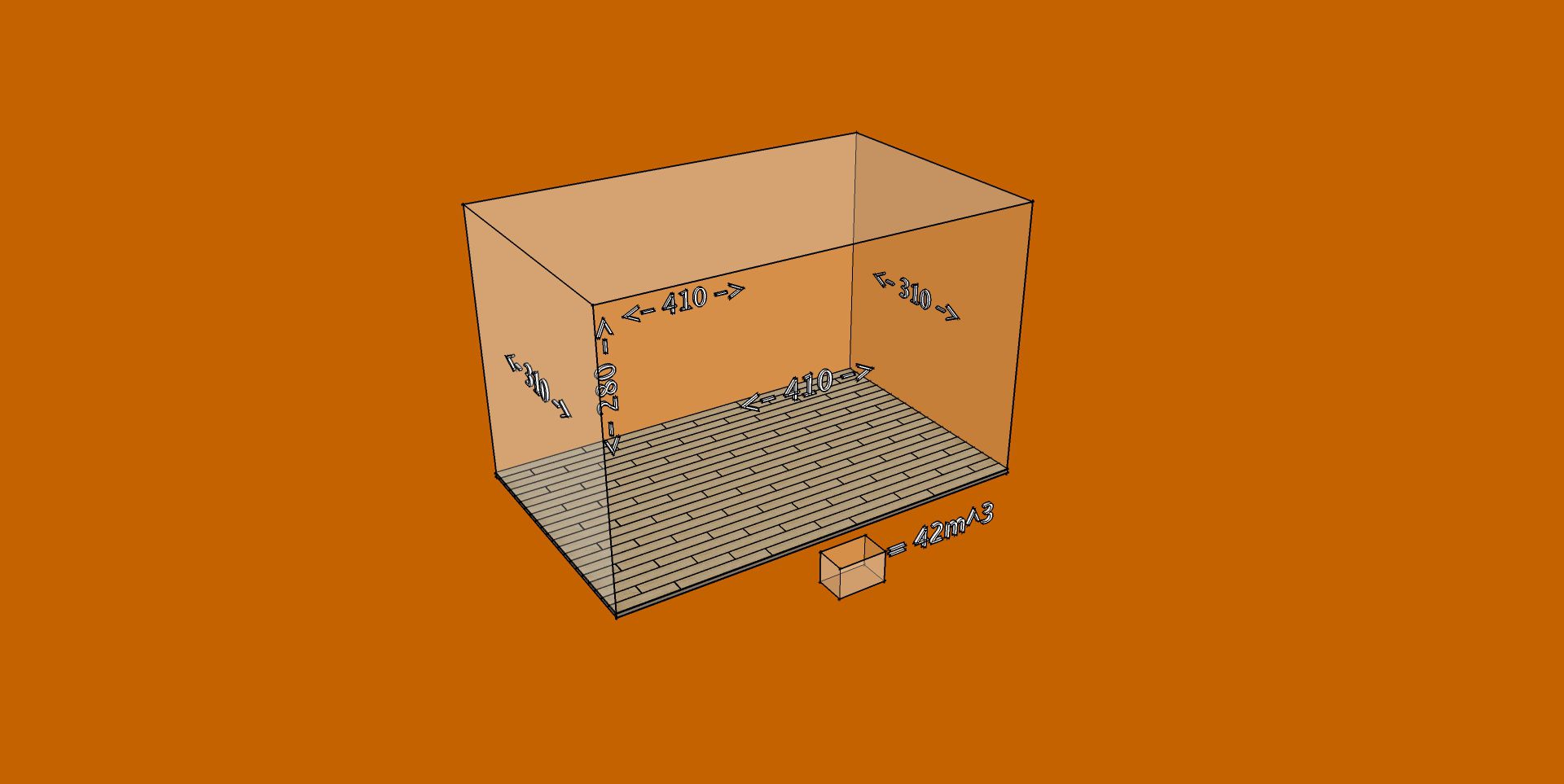

A small room, for our practical purposes is one that is smaller than 42 m^3 (1,483 cf) measuring around L410 x W310 x H280 cm (L13.5' x W10' x H9'). (See Fig 4.)

Fig 4: Any room measuring less than these dimensions is considered small acoustically.

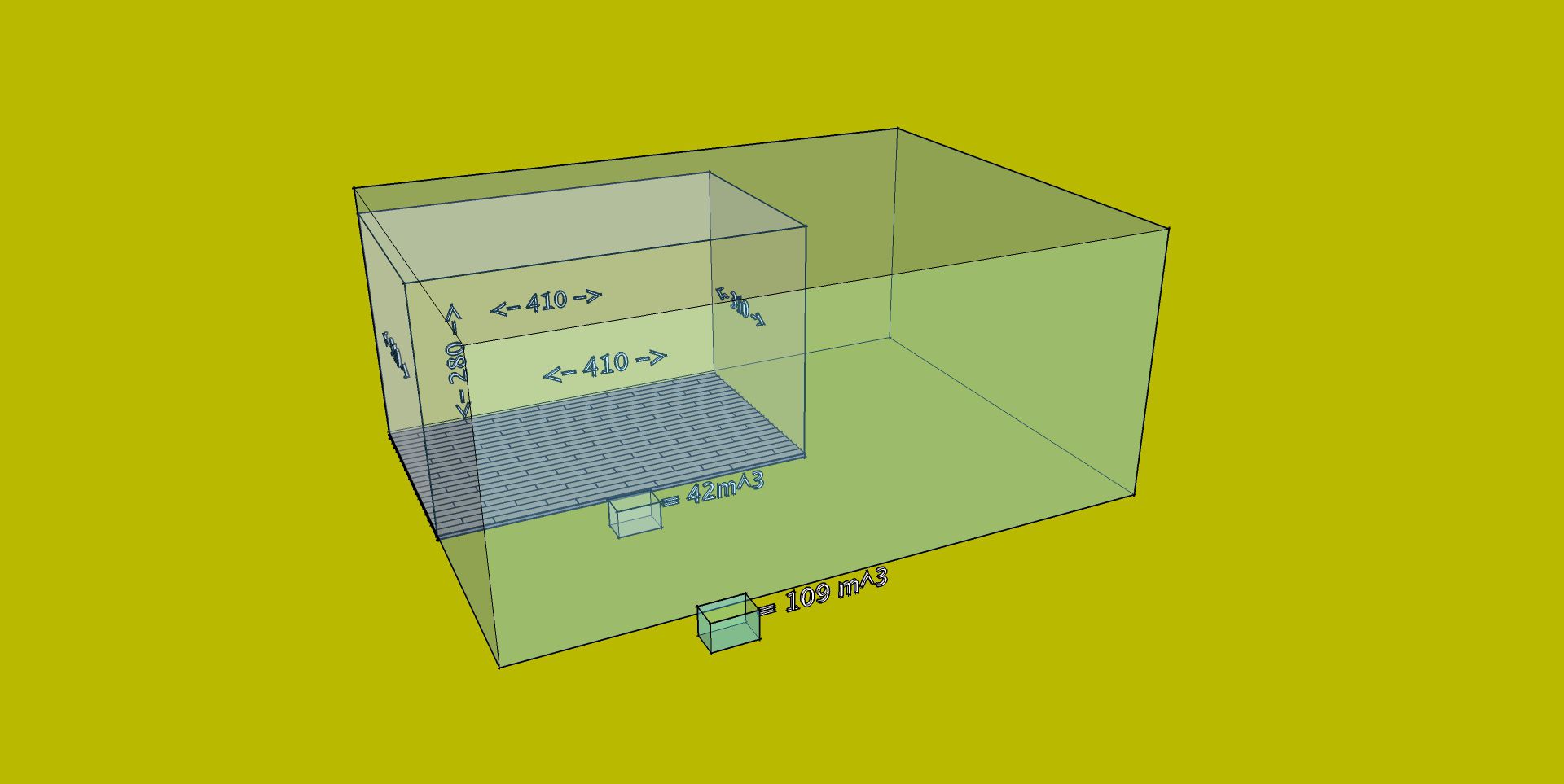

By contrast a room L700 x W520 x H300 cm with a volume of around 109 m^3 (L23' x W17' x H10' @ 3,850 cf) is considered an ideal starting point and has more than twice the volume of an average bedroom. (See Fig 5.)

Fig 5: Comparing volumes of a small and a theoretically ideal room.

These dimensions (and larger, while maintaining the same ratio) are rare these days for the average project studio, so it is clear from this physical fact that most of us are working in less than ideal acoustic spaces.

If you are setting up in a space as large, or larger, count yourself lucky, you one-percenter.

Size does matter, and <7 Inches will do

It is a general rule of thumb that the larger the drivers in your system are, the further you need to sit from them to find the sweet spot.

Conversely, the smaller the speakers get, the closer you can sit to them, as mentioned above. You can also space them nearer together without collapsing your stereo image because it is far easier to adhere to the equilateral triangle listening position recommended by most manufacturers.

Fig 4: The Recommended distance from nearfield monitors - speakers the same distance apart as you are from them, toed inwards 30°.

The industry standard near field Yamaha NS-10 has 180mm paper woofer (for you imperialists out there that's a 7” speaker diaphragm), a 35mm soft-domed tweeter and a frequency range quoted from 60 Hz to 20 kHz.

Another industry standard for mixing are the Auratone 5C mixcubes at 114.3mm (4.5”) and a frequency range of 75 Hz to 15 kHz.

You will notice that both are notably lacking in low end reproduction. Even at moderate levels, say 50 - 70 dBSPL, these speakers are less likely to drive acoustic anomalies from the room into your ears.

And that is the beauty of working with small monitors, you can listen quite loudly to them, but they are physically incapable of pushing too much bass energy into the room.

Speaking of low end reproduction, what about bass?

The industry recommended standard for optimal listening is 85 dbSPL and most small speakers are spec'd to push at least 95 dB, so trust me, loudness is not an issue.

The big question is: How exactly do they perform, you know, down there?

In the next part I will go over some, light, non-math, science related acoustic issues in small rooms, Hi-Fi vs. nearfield speakers, the difference between monitoring and feeling bass, and finally, touch on the pros and cons of adding a subwoofer to your setup.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!