I know a lot of musicians and songwriters who work as one-man/one-woman bands, laying down all (or most) of their tracks themselves, but a lot of them still draw the line at doing their own drum parts. “Oh, I can’t really play/program drums”; “I can’t seem to get them to sound natural”; “I never know what to do for fills”; etc etc - these are their common laments, and sometimes those complaints make me want to pull my hair out, because basic drumming/drum programming is not really as difficult or mysterious as they seem to think.

Just as drummers learn “rudiments” - basic stick techniques - non-drummers who might want to create their own parts shouldn’t find it that difficult to get the hang of at least basic beat-making, along with enough variations to not only keep a part interesting but also make it feel like it’s responding to the rest of the instrumentation in a musically appropriate and effective way. Of course, there are many tools that generate good, real-sounding drum parts from prerecorded patterns or intelligent programming, but for those artists who might prefer to play (or at least create) all their own parts from scratch, here are just a few drum basics for reluctant non-drummers..

The Backbeat

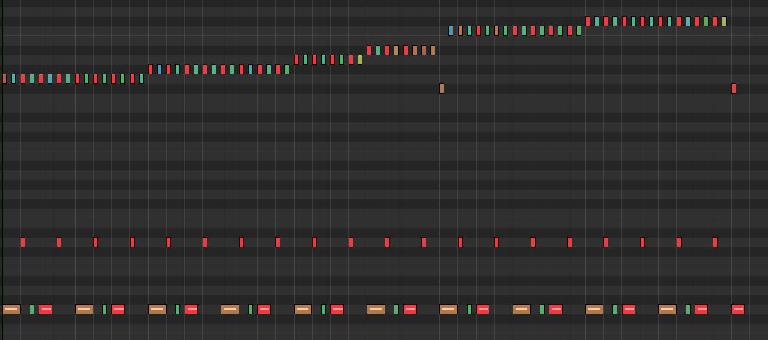

Anyone who taps along with their favorite songs already knows how to tap out the standard backbone of 90% of pop songs - the backbeat. This is the back-and-forth pattern that goes between (low-pitched) kick (or bass) drum, and (higher-pitched) snare drum - in common (4/4) time, the kick hits on the 1 and 3 (of each 4-beat bar), and the snare on the 2 and 4 - the backbeats.

This very simple pattern is the basis of most of the somewhat more complex accented and augmented patterns that drummers actually play most of the time, but even this simplest-of-all-beats can serve just as is it - case in point, the very basic but effective beat in the Michael Jackson song “Billie Jean”. Common variations of the standard backbeat may put a kick on all 4 beats - the “4-on-the-floor” of much dance music, both with and without the backbeat snare hits. Music styles that tend to use (or sound like they use) live drummers typically have additional elements in the pattern - back to that in a minute..

Timekeeping

The other main element of a drum pattern is the basic timekeeping done on one or more cymbals. Most commonly this would be the hihat, but the ride is also used when the beat needs a little more “push”, like in choruses. The most basic contribution of the hihat (or ride) to a basic backbeat consists of either steady quarter-notes, eighth-notes, or even sixteenth-notes (eighths are the most common - 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & ) along with the quarter-note kicks (1 & 3) and snares (2 & 4). But while this may seem like the simplest, most mechanical part of a pattern, it’s actually one of the areas where there may be the most (subtle) variation, and often this is the first element that can help a basic pattern “groove” better, sounding less mechanical - more loose and “musical” (at least for musical styles where that’s the desired effect).

Hihat Variations

The hihat, of course, consists of two cymbals controlled by a foot pedal. Pedal down tightly provides closed hihats - the two hats touching for a short, tight (fairly) bright “chunk” sound. Fully open gives a long, splattery sound, as the hats beat against each other. In-between those two extremes are a whole range of partially-open sounds - a slightly longer chunk (closed but looser), a partially open sound, a slosh (partially open but a little looser still), etc. Different sampled drums may have from 2 to 3 to 4 or more different hihat open/closed variations (for example, Logic’s Drummer DKD drum kits have 7 for each of three sticking variations).

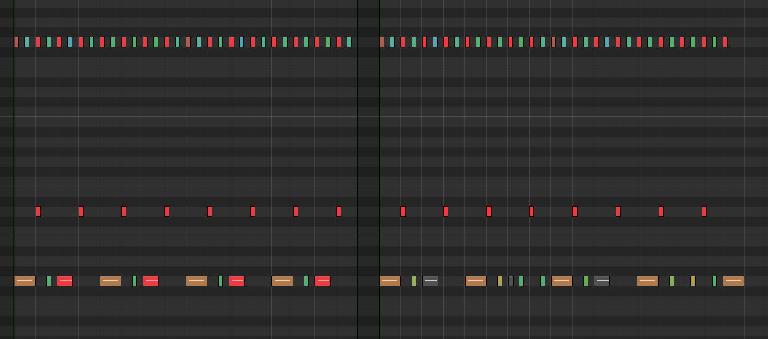

When drummers play a basic timekeeping hihat part - let’s say a typical 1/8th-note part - they tend to accent the hits that fall on the beats (1, 2, 3, 4) a little more than those that fall in-between, on the “&”s. This is one of the first things that can distinguish an intentionally-programmed-sounding dance-music-style hihat part from a live-drummer-style part.

Live drummers also tend to work the pedal very subtly. A simplistic way of doing this is the alternating closed/open hihat of classic disco beats, but a more subtle version might use a slightly-looser closed hihat chunk on the accented beats than on the unaccented ones - sometimes this variation is programmed into the instrument as velocity variations, but if not, then a pattern that varies between the appropriate keys for two slightly different closed hihat sounds can do the trick.

Over a longer song arc, many drummers gradually open the hihat a little more as the song builds in intensity - besides the obvious “switch-from-hihat-to-ride-in-the-choruses” gesture, this might also include shifting to a slightly more open closed-hat on the second verse, or easing into a gradually longer slosh (partially open hihat) leading into transitions (i.e. verse-to-chorus) or fills. Ride variations range from playing the ride near the edge (the basic ride “ping”) to closer to the bell for the cymbal (more of a “clang”, possibly appropriate for more aggressive/energetic sections of the song).

Work The Kick

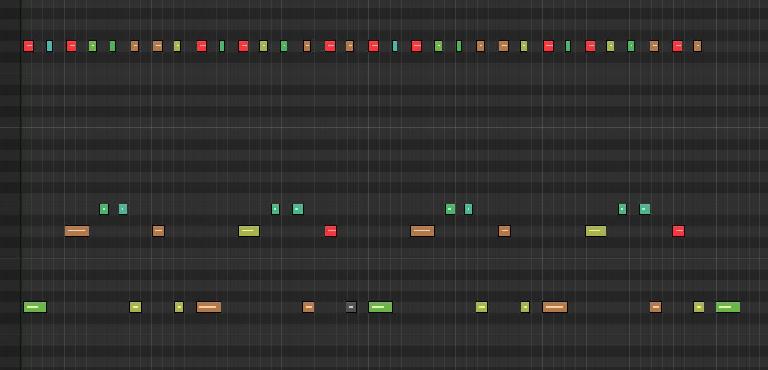

Of course, while a subtly varied hihat part can make even the most basic 1/2/3/4 backbeat a bit more “musical”, most of the time (outside of some dance music) there are also variations in the kick that help to define the drum pattern for a particular song. The most basic kick variations add an extra 1/8-note before or after the kick on “3” - so the patterns in Ex. 5 would be very common.

Many novice drum programmers pick one variation and stick to it, but drummers (and more experienced programmers) tend to mix them up - not willy-nilly, but in an organized, musical way, often to create a somewhat more complex repeating pattern that spans 2 or even 4 bars. Often, additional lighter hits - eighths or sixteenths - are added as lead-ins; sometimes light lead-in notes like this are referred to as grace notes (they’re also commonly used with snare parts).

Syncopations

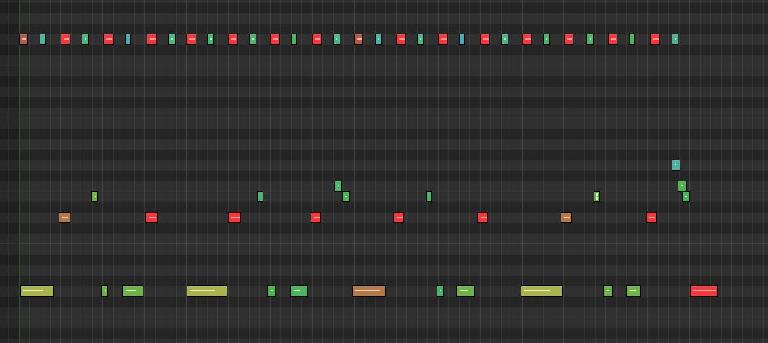

In regard to drum patterns, a syncopation is an off-beat - a note (or notes) that would be expected to sound on a certain beat (or sub-beat) that instead is played a little early (or late).

The Backbeat

In much pop music, the snare is one of the more steady, regular elements of the beat (fills aside), maintaining the solid (2 & 4) backbeat of the pattern, but here as well subtle and not-so-subtle variations also make for a variety of more interesting patterns. Snare syncopations are common, often in combination with a more varied kick pattern (that may also contain syncopations) - a lot of modern music is based around these kinds of heavily-syncopated patterns.

Another common snare variation is the use of grace notes - short, light notes leading into louder accented notes. Sometimes these may be used as an alternative to kick-drum figures, creating a bit more back-and-forth feel in the basic pattern. Real drummers also sometimes drag the stick across the snare drum lightly for a more “sustained” grace note, that’s actually a quick series of quieter notes that run together - these are called “drags” or “ruffs”. They may be a little difficult to play live on a keyboard or set of drum pads - having the same snare drum sample assigned to several (non-transposing) keys can help, and some of the more comprehensive drum instruments include prerecorded samples of these special techniques.

Crash Test

I’m running out of space here, so I’ll wind this up with a brief mention of the crash cymbals. Naturally these are (usually) not part of a basic drum pattern, but they’d still be used reguraly for accents, at appropriate moments. Obvious times for a crash are at the beginning of a new section, or the end of a fill, but they can also be used lightly for intermediate-level accents at soft transitions (i.e. Verse 1 A->B). At the other extreme, sometimes a drummer will actually keep time on a (smaller?) crash, to add some splashy energy to a more intense musical section.

Time Out

Obviously, this has been just a very basic, preliminary look at drum programming and tweaking, but for those who really think that beatmaking is too far outside their wheelhouse, hopefully it will have provided a few suggestions that might come in handy for some intrepid producer’s initial foray into the art of the beat.

Learn more about drums and beat making in the AskAudio Academy here.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!