Listening beyond music

First and foremost, take good care of your hearing. Don’t poke around in your ear canals with cotton earbuds or a rolled up tissue, as this might force earwax deeper into the canal (where it doesn’t naturally occur) and push it up against your eardrum leading to hearing issues: if it’s smaller than your elbow it shouldn’t go in your ear. Stay away from esoteric “cleanses” like ear candles, they are dangerous and can lead to serious and permanent harm. If your ears really need to be cleaned go to a medical doctor.

Second, limit or stop listening to mobile music, especially with in-ear headphones. If you insist on listening to music on the go, listen at reasonable levels with a decent set of on or over-ear headphones, and take regular breaks from listening.

Third, book yourself a check up with an audiologist, mention that it is for music production, and let them know you want data on your full spectrum of hearing. Hopefully you will get a clean bill of health, or at least you will know if or where there are issues in your own physiology.

Fourth, be constantly aware of sound levels rising and falling around you, it is amazing how little people protect their hearing from daily, intrusive sound sources.

And finally, always limit direct exposure to excessive sound pressure levels, not only during recording and mixing sessions or when out with friends, but also when passing construction sites or sitting in heavy traffic. Invest in a decent pair of earplugs and carry them with you everywhere you go. You can never be sure when you will be exposed to damaging levels of sound, especially if you are active on a live music scene, regularly visit bars and clubs, or attend large sporting events.

Active vs. Passive Listening.

For our purposes, active listening means being consciously aware that you are listening to something to better understand it, or learn from it some in some way.

Passive listening is switching off the “analysis mode” and just enjoying music, a movie, or a TV show without picking out all the poorly mixed and edited ADR, recognising stock foley effects, and raging on sound editors who still think it’s hilarious to slip a wilhelm scream into every major battle scene.

Listening outside.

There’s a lot of music playing everywhere, from buskers to in-store systems to other people playing music too loud in their headphones. Listen to that music.

How does a track you know well sound playing through the cheap ceiling speakers in the local grocery? Or in the restaurant over the noise? Which instruments stand out? Which frequencies are exaggerated? Is it the sound system? Is it the mix? Is it the genre? And also importantly, why are those factors noticeable and working, or not working?

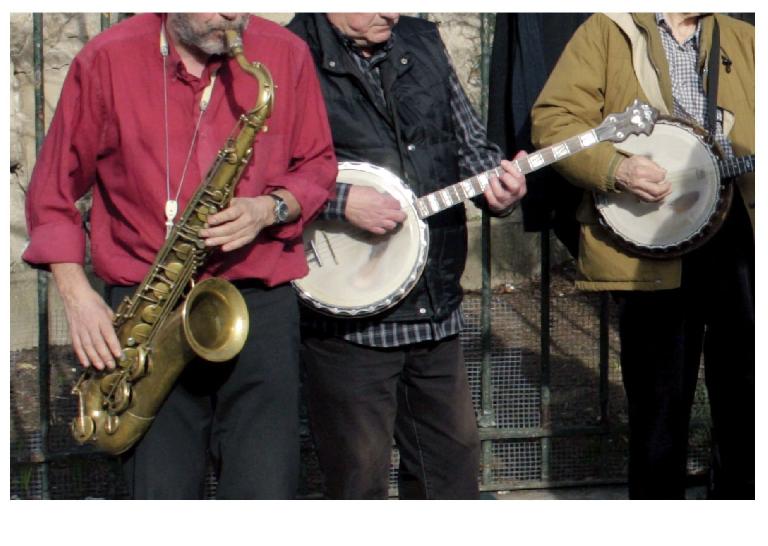

Street Musicians

How would you recreate that vibe and ambience in a mix? How would you capture their sound? How is their tempo, timing and tuning? How is their phrasing and voicing? What would you want to suggest to them if they were sitting beyond the glass and trying to lay down this song? Do they strum very high up towards the neck, or low down by the bridge (could you tell without looking), furthermore, every now and then they clip the sound hole with the pick? How would you handle that transient “mistake” in the mix?

Is it part of the performance to be accentuated, balanced or suppressed? What does their overall “sound” lack frequency wise, if at all, and if it does, why? Is it their set up, their instruments or the environment, or is it within the performance itself? How would you personally improve or enhance any of these perceived shortcomings? And crucially, would your sonic solutions benefit the artist and audience at all? Now listen to your favourite artists and records and ask the same questions.

Listening inside

The following advice presumes you have made at least a rudimentary effort to position yourself and your speakers as correctly as possible in your room, and assumes little to no acoustic treatment. First, create a reference level. How can you know when something is loud or soft when you have nothing to compare it to? With a fixed reference level you will be able to tell instantly when something is too loud or too soft.

The simplest solution is to turn up your system until you find a level you (and your neighbours) are comfortable working at and ALWAYS return to work at that that level after turning up or down for any reason. If you are more serious, you can look into calibrating your setup properly, but note that the reference level of 85dB SPL that is often mentioned is specifically for large mix rooms: a more realistic target for small rooms is between 70 and 74 dB SPL at the listening position. You are looking for a sweet spot where your sound system works with your room not against it.

Second, familiarise yourself with your listening environment.

Of course a good monitoring system and acoustic treatment of a critical listening space is highly recommended, but any problems in a decent (bed)room with common small room acoustic issues can be somewhat overcome by “learning” the room and compensating mentally for the shortcomings of both. In other words, once you have set a reference level that works for you, listen to a crazy amount of (loudness level adjusted*) music that you know very well in the room you want to mix in. A CRAZY amount.

Listen for as many hours as you can afford, and you will soon get a solid feel for how mixes you admire sound in that particular space. Coupled with your known, fixed reference volume it will become obvious when any audio elements played in your room are too loud or too soft. The idea then is to get your own mixes to sound similar to your (loudness adjusted*) reference tracks in that room, and then check your mixes on as many other systems as possible. Easier said than done of course!

*A common mistake when referencing professionally mastered tracks is to try and match loudness when the reference track is there to match the balance of elements in the mix. Always loudness level (match the levels of) “hot” tracks so that you are focusing on the mixes themselves not the difference in levels between them and yours.

Listening to details

Training to accurately identify which frequencies are causing an issue in any given element takes years, and it may seem almost impossible at first, but there are resources out there to get you started.

EQ “cheat” sheets

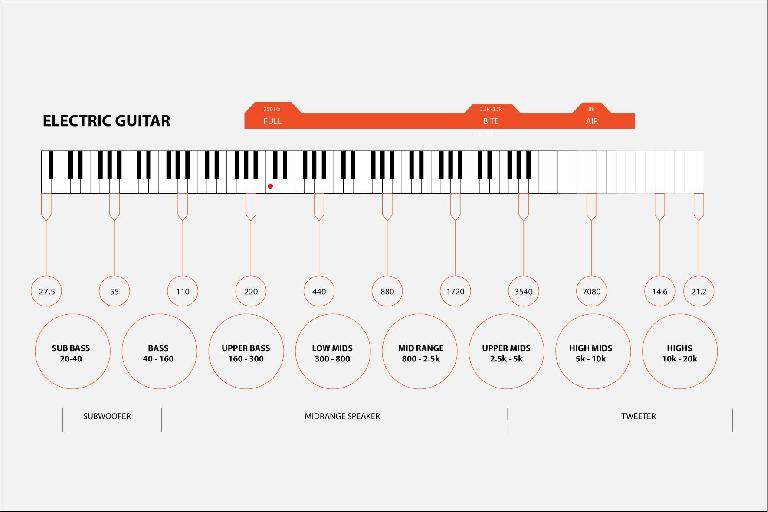

Use them, reference them, eventually it will become second nature if you keep at it. Familiarise yourself with the general behaviour of the overall ranges – low end, low mids mid-range, high mids, high end – and learn what generally happens if you boost or cut them across a whole stereo track. Then go onto EQ charts of the instruments you will be mixing most often and learn what happens if you boost or cut their respective ranges too.

It is really useful to develop a core knowledge of the average range of the instruments routinely used in your given genre because even though every instrument and recording is unique, there are well known “problem” frequency ranges for almost all instruments and knowing them will narrow your focus to key areas of probable issues and make finding the actual problem frequencies much easier. After reading up on the range of an electric guitar for example, you may notice later in a mix that the guitar is kind of weak and thin and lacks “presence” in the mix. Where would you boost (or cut) to address that observation?

If you have done your homework you will know that “fullness” in electric guitars generally resides between 250Hz and 500Hz, but in the overall mix so does muddiness (at 250 Hz) and “honk” (at 500hz). So if your guitars are feeling thin guess what, you can immediately jump to that range and see if cutting or boosting helps. Boosting at 1.5 kHZ to 2.5 kHz may add the presence you are looking for. Conversely, cutting frequencies before and after the known ranges might do the trick too… this is where the art of mixing kicks in.

EQ charts take a large portion of the guesswork away and start you on a path of making informed EQ decisions. As you progress you will form your own “sonic memory” of what “honkiness” at 500 Hz (or thereabouts) sounds like, or where “nasal” frequencies in vocals tend to hang out, and you will start to find troublesome frequencies with greater speed and accuracy until you don’t need to look at a chart at all.

Now go back outside and listen for these known frequencies in the wild. What EQ range exactly is the “grocery store speaker” exaggerating or attenuating for example, and how would you utilise that knowledge?

Conclusion

This article is a very convoluted way of saying that every waking moment can be training for your ears. It takes time and effort, but you are in complete control over when you want to passively or actively listen, and thus any situation involving sound can be turned into an ear training session.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!