Compression is, of course, one of the most widely-used tools in audio production, despite being a bit challenging initially to get a handle on. But the majority of engineers and producers—from pros to hobbyists—do get the hang of it and become compression mavens, using it to craft punchy, dynamic mixes and masters. But there is a type of compressor that many may find a little more difficult to get comfortable with—the multiband compressor. Here’s a brief look at that particular processor.

More Is Better

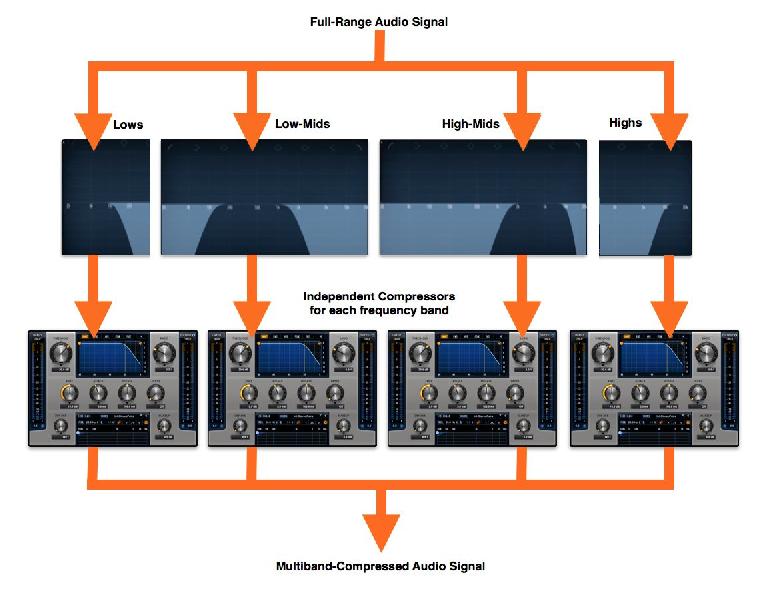

A multiband compressor is basically three or four separate compressors working together, each independently processing a different frequency band within the 20Hz-20kHz range. You could theoretically make your own, by running an audio signal through a crossover, dividing it into (typically) three or four frequency bands, and then sending each band through its own compressor.

In fact, as the story goes, back in the day that’s what radio stations—widely hailed as the originators of multiband compression—did; it provided them with greater control over full song mixes, enabling more in-your-face sound, without signal overages (for which they could be fined by the FCC).

Modern multiband compressors are available in both hardware and software formats.

A typical multiband will have three, four or five user-adjustable bands. Common usage would divide the frequency range into a bass band, up to around 100Hz or so; a lower-midrange band, where the bulk of the music—fundamentals and lower harmonics/overtones—lives, from around 100Hz up to maybe 2 or 3kHz, give or take a kHz or two; an upper-midrange band, for presence—maybe 2 or 3k to 8 or 10k; and a high-frequency band, for “air” and brightness, from 8 or 10k up.

Compressing the audio in these bands individually can provide greater control over different elements in a complex signal—like a full mix—as well as offer better control over wide-ranging signals. A traditional technical use that illustrates the advantage of a multiband over a single-band compressor is to compress strong transients without inducing unwanted “pumping”—where the level of the entire audio signal is pumped up & down unintentionally in response to an instrument’s repetitive strong peaks, instead of just controlling the one element that needs it.

The classic example is an overly aggressive kick drum thumping away while other instruments play along—if a single-band compressor is employed to tame the kick, a common problem may be that every time the kick hits, the other instruments are pulled down with it—they “pump” with the kick, an unwanted side effect. A multiband compressor could be set to provide more gain reduction in just the lowest band, where most of the kick’s excess transient energy is, pulling down just the thumps without dragging down the other parts, which have most of their energy in the other, midrange bands.

Multiband Layout

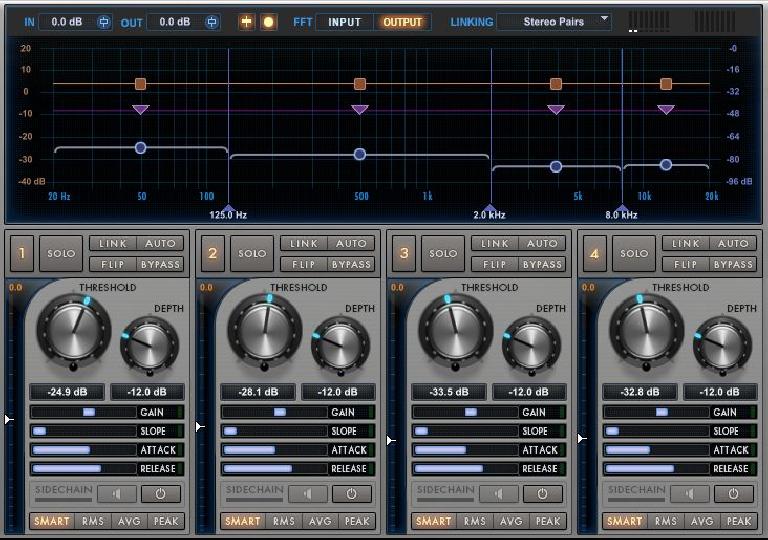

A typical multiband has 3-5 bands, with each one usually having all the same controls as a single-band compressor—threshold, ratio, attack, release, make-up gain, and often knee (I’ll assume everyone is familiar with the controls and operation of a standard single-band compressor).

Sometimes there are additional controls, or a slightly different layout. Depth controls might be included, setting a limit for maximum gain reduction on only occasional very strong peaks, again to selectively avoid pumping. Some multibands also include upward compression, where lower-level signals are raised rather than high-level signals being lowered. The result is still dynamic range reduction, but the processing is applied to the quieter parts, rather than to the more prominent louder portions of the signal.

Naturally there are controls specific to multiband operation. Each band may have a Solo and Bypass button. Solo will isolate just one or more bands, letting the user hear exactly what part of the audio—instrument range or mix components—are most prominent in that band; this is a good way to get acclimatised to multiband operation. Bypass doesn’t mute a band, but turns off compression in just that band, in case you want to only process a particular range—like in my kick drum example above.

For the most part, the controls should be familiar to anyone used to regular compressors; the “trick” is getting used to how a multiband compressor affects the different frequency ranges and the different instruments in a full mix, in order to get the most out of it.

Multiband Applications

A multiband compressor can be used on any signal, especially one with a wide frequency range, where separate parts of the sound or strong localized resonances might benefit from processing that targets just particular areas of the overall audio signal. A full drum kit would be a good example. If you had, say, an old-school stereo drum recording (two or three mics, like the Glyn Johns method), and some of the drums or cymbals were not in the the best balance, a multiband might be useful.

If the drums were captured primarily with overhead mics, cymbals—especially crashes—might be a little loud when they’re occasionally hit, and the kick might be a little too soft or thin-sounding. EQ could help, of course, but pumping up the low end and dialing down the highs with a static EQ might be too much, dulling down and muddying up the overall drum sound, when those adjustments were really only needed occasionally. In that case, a multiband compressor can act as a “dynamic EQ”—a common description, in fact.

Setting the high-frequency band to kick in only when the too-loud cymbals hit could potentially tame them at those moments, leaving the rest of the drums mostly intact, and not dulling down softer cymbals like hihat, which may be just fine. Likewise, the low-frequency band could be set to pump up the kick (fast attack & release) a little without overly thickening up the snare (in the midrange bands) on the alternate beats.

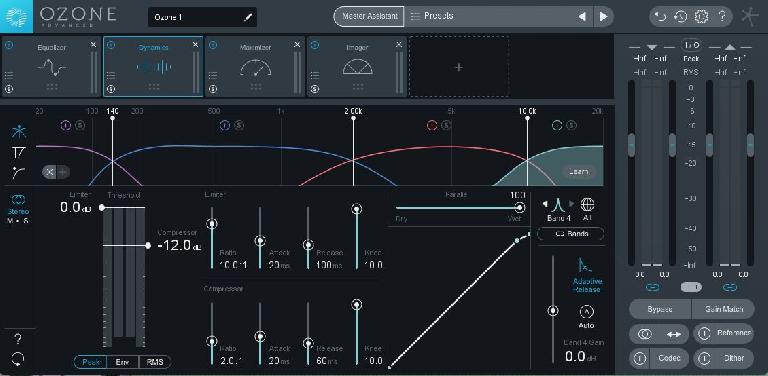

Mastering

By far the most common application for multiband compression nowadays is mastering. The potential benefits should be obvious—multiple instruments in a full mix may primarily occupy different frequency ranges, allowing for some degree of greater control over individual elements.

For example, some softer electric rhythm guitars or a keyboard/synth part could be brought up a little without overly accentuating the lead vocal, which also shares the upper-midrange presence band. If the threshold could be set to keep the usually-louder vocal in check without hitting the guitars, then that band could be cranked very slightly, adding presence to them while the compression keeps the vocal in proper balance when it comes in. In the same band, if a fat snare’s transients were too overpowering, stepping on the vocal, then maybe they could be quickly clamped down in the lower-mid bands, without affecting the voice too much.

Taking a more overall view—and keeping in mind the idea of a multiband compressor as a “dynamic equalizer”—one could be used to, say, impart an overall tonality—like a gentle “smile curve”—that’s applied dynamically, for a more subtle tonal tweak. Different threshold settings in the different bands might be found that would compress, say, the lower mids more aggressively, leaving more energy in the lows and highs.

In fact, this tends to be the case if you set all the bands with the same settings—since there’s usually more energy in the mids, all things being equal they’ll get more compression/gain reduction than the highs & lows, creating a fatter/brighter mix. By tweaking the individual thresholds, you can make this more subtle, and target it more to sections where it may be needed. For example, if you had a mix that was mostly well-balanced, but in some dense louder sections the mids tended to swamp detail, setting the mids’ thresholds to clamp down a bit just in those sections might clean up the excess midrange thickness only when needed, providing a little welcome clarity in those passages, but leaving other sections of the song alone, where the mix/balance is already fine as is.

With Great Power...

While multiband compression can be a great tool if used wisely, anyone new to it should be careful not to overdo it, especially on a full mix. While it can afford the opportunity to exert greater control over a track or mix, multiband compression can very easily over-process the signal if not used judiciously. When getting acclimated to it, liberal use of the plug-in’s overall bypass button would be well-advised; it’s easy to get carried away and over-process, when very small, subtle tweaks are what’s really called for. But once you get a handle on it, multiband compression can be a valuable addition to any mixer or producer’s toolbox.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!