The latest high-end, high speed computer connections—Thunderbolt and USB3—promise the possibility of ultra-low latency settings, and manufacturers are quick to tout that advantage. But outside of the ranks of more tech-savvy DAW operators, many producers and engineers only have a basic understanding of Latency. While they know that, in general, low latency is a “good thing”, they’re not quite sure just how low they should go, or try to go, or what practical effect that may have. Here are a few considerations to bear in mind when deciding what the optimal latency setting should be for a DAW setup, from the standpoint of its potential musical significance.

Delay That

A quick primer (or refresher): Monitoring Latency is the (inevitable) delay in an audio signal passing through a computer/DAW. Technically, latency means “wait time”, and it’s a result of the technical process by which audio is recorded and played back in any digital audio rig. There’s always some amount of latency present, but it can range from vanishingly small and virtually imperceptible to enough of a lag that musicians can feel like they’re hearing their part as a slight echo in the headphones. In simple playback situations like mixing with nobody performing live, it shouldn’t be noticeable at all, but in live recording sessions, where the player/singer is monitoring their own part while playing as it’s running through the computer/DAW, then it can potentially be audible, and possibly problematic.

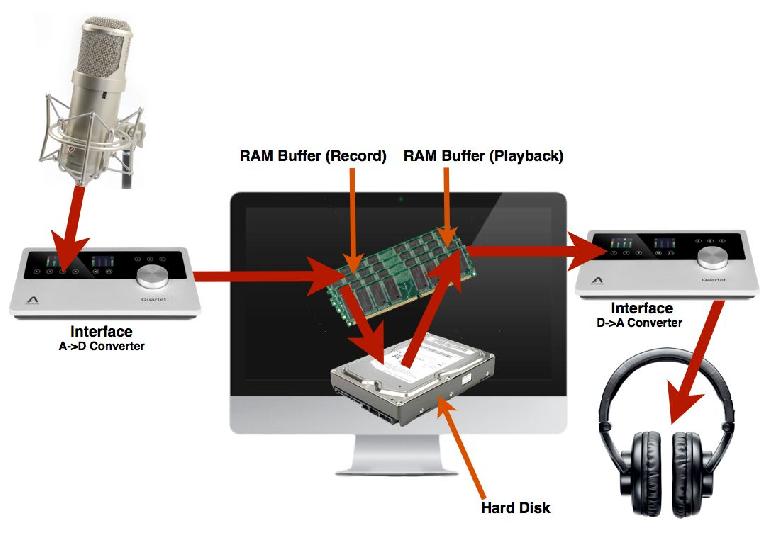

There are a few technical causes of latency. The A-D and D-A converters in interfaces all produce a very small amount, but that’s typically only about a millisecond or so, which is insignificant from a musical standpoint. The bulk of latency is caused by the digital audio signal being passed through the computer’s RAM on its way to be recorded to and played back from the slightly slower mechanical hard disk.

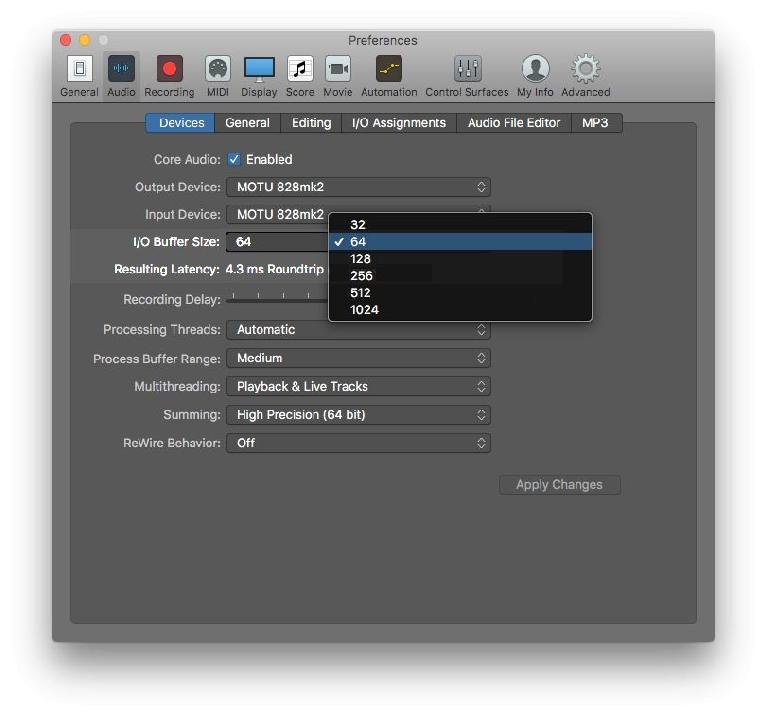

RAM buffers are set up to insure uninterrupted flow, avoiding clicks and glitches. That’s the setting you must make in the DAW’s Audio Preferences—the size of the RAM buffer, in individual digital samples.

Larger buffer sizes take the strain off the computer, for more reliable click-free performance, but introduce potentially problematic amounts of latency, as they constantly fill up with and empty out the streaming audio. Smaller buffer sizes lower the latency, but every computer has a point where buffers below a certain size are just too small, given the capabilities of that machine’s hardware and peripherals, and clicky, glitchy audio results. The problem may be almost constant, or only very intermittent (making it harder to troubleshoot), but it means that that system has reached its limits. Faster connections are a big factor in being able to set the buffers for lower latency while still maintaining reliable performance, but if any component is a weak link (like a 5400 rpm Hard Drive or a drive that’s too full), that can be the deciding factor.

Naturally, since music is all about timing, nobody wants latency to possibly interfere with capturing the best performances, so—at least for recording sessions—it’s important to set the buffers for the minimal amount of delay possible. Note that in some situations there are other solutions, like analog (zero-latency) monitoring, but given the widespread use of virtual signal processing nowadays, I’m going to assume that with most sessions recorded audio must pass through the DAW, making minimal latency a necessary part of the setup.

How Much Is Too Much?

Humans don’t really perceive very small latencies. Depending on the signal, delays of less than 10-12 milliseconds (ms—thousandths of a second) are not usually enough to be noticed. If a performer is hearing the signal he/she is creating with under 10-12 ms latency, they’ll probably just unconsciously compensate for any subconsciously perceived lag, and adapt their musical timing to be able to play in good sync with other parts.

To put this in context, there’s always some acoustic latency present when musicians play together in a room, and they normally adapt without thinking about it. Sound waves in the air travel at a fixed rate of around 1 ms per foot. So if two players are performing acoustically in a room and they’re 8 feet apart, by the time player A hears player B’s part, it’s 8 ms later than when player B heard it, and vice versa, yet they’re able to play together in good musical time. Fortunately our hearing is not that acutely sensitive to variations in timing that small. We do perceive them subconsciously as normal human imperfection, but from a musical perspective, they don’t interfere with being able to maintain tight timing, and laying down a solid groove.

Your Mileage May Vary

That said, even before latencies reach that (roughly approximate) 10-12 ms point, some musicians may be more sensitive than others, given the nature of the musical sounds they make. Players of percussive instruments like drummers may be bothered by even small amounts of latency that others might not notice, due to the sharp attacks of drums and percussion instruments. In the studio I’ve had drummers comment on latencies of only around 6-8 ms, which most performers are oblivious to. I figured out that this was in part due to the fact they they were also hearing their notes acoustically - getting a better headphone seal and cranking the level in the cans until it dominated helped, enabling them to subconsciously compensate for any subliminally-perceived lag they felt between feeling the stick hit the drum and hearing it in the monitor mix.

But in most situations, moderate amounts of latency will be just fine: typically around 8-12 ms may work for most situations, and this won’t require the absolute lowest buffer sizes offered, maintaining a good compromise with the average DAW computer between low latency and reliable recording and playback. But if you determine that there is a need for lower latency, then you need to know ahead of time the minimum latency setting—the lowest buffer size—that your particular rig can handle with complete reliability. This needs to be established for the rig ahead of time, not during an active session, so a little testing is in order when initially setting up a DAW studio.

How Low Can You Go

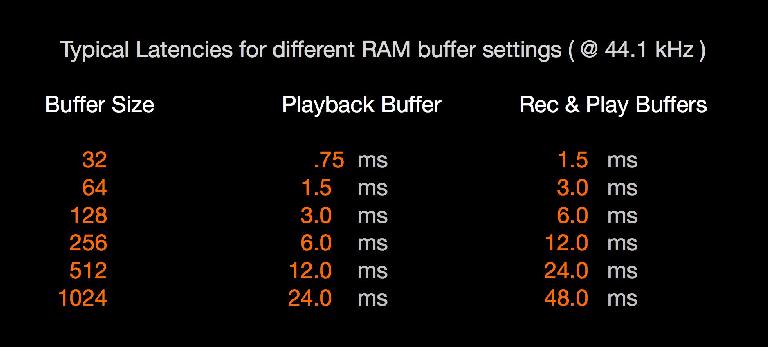

So how does this talk of milliseconds latency relate to the buffer sizes you’re presented with when making this adjustment? It’s a function of buffer size and Sample Rate: the chart below lists the amounts of latency at 44.1k SR for the common buffer size options.

Note that there are two buffers, one each for the incoming (recording), and outgoing (playback) signals. During a live recording, the audio passes through both, but a MIDI-triggered virtual instrument would only be subject to the latency of the Playback buffer (though MIDI may add some small delay as well).

With most smaller rigs, a 64-sample buffer setting might be the goal for recording sessions—adding the AD/DA converter’s latency (and the possibility of additional software buffering, which some interfaces add), you should be getting a total round-trip (input/output) latency of around 4-5 ms or so. If you’re monitoring in speakers, add another 3 ms or more (sound in the air = 1 ms/foot, remember?). If that setting produces glitches, then a 128-sample buffer usually solves it, and the approximately 7-8 ms latency should still be fine for the majority of performers.

If the system still glitches, then you may be getting into a potential problem area. A 256-sample buffer may be acceptable to some musicians (especially for V.I. use), but not to others. Personally, as a player, it bothers me just a bit and while I can perform, I feel like my timing is not as tight as it should be, though others have been just fine with it on the same rig. If the buffer size puts the latency at or above that 10-12 ms point, then headphone monitoring is definitely in order, and if the DAW Preferences offer an option for enabling/disabling any extra safety buffer, turning it off might help. Also, watch out for any additional latency coming from the player’s rig itself: laying down a guitar part through a POD added a few extra ms from the POD’s processing, on top of the DAW latency, so for me a 256 buffer was ruled out in that scenario—I had to switch to analog monitoring, foregoing any native DAW processing on the signal during recording.

The Cutting Edge

With modern DAWs and interfaces, there’s usually even a 32-sample buffer option available. This should bring overall roundtrip latency down to the 1-3 ms range, the bare minimum, as in dedicated hardware-accelerated high-end digital recording gear. Here, the critical factors will be your computer’s age and the interface’s connection type. Three or four-year-old computers may glitch out, but this year's (or last year’s) model might do fine, providing your interface is hooked up via a high-speed connection: as above, Thunderbolt or USB3.

With older connections like FireWire or USB2, the very low latencies of a 32-sample buffer may be out of reach, though it couldn’t hurt to try (again, way before the session)! But if you’re hanging onto an older interface (on the if-it-ain’t broke plan), like a FireWire 400 model, even hooking it up to a computer Thunderbolt port with a suitable adaptor will almost certainly be a no-go for the lowest buffer sizes—64 (at best) or 128 would probably be the most reliable option, and that should be just fine 99.9% of the time.

So when you’re shaking out your new DAW rig, don’t forget to spend a little time on the buffer setting, and be sure to try out the different settings as a player (or with a player, if necessary)—don’t just go by whether you get clicks and glitches, make sure the rig feels comfortable to lay down mission-critical parts through—after all, that’s the whole point of low latency recording.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!