They say “nothing is more permanent than temporary”. I'm not sure anyone quite knows who “they” are, but it could be said they've got their finger on the pulse of musicians who build and use templates. Orchestral template, big band template or otherwise, the purpose of building a template almost goes without saying, but let's lay it all out on the table: a template is meant to provide easy recall of (typically) a large palette of sounds that we use most regularly. A template's design also usually reflects a fair number of important decisions about audio signal flow within your DAW—decisions made in anticipation that they'll provide a consistent and familiar engineering/mixing environment to serve the needs of many different projects over time.

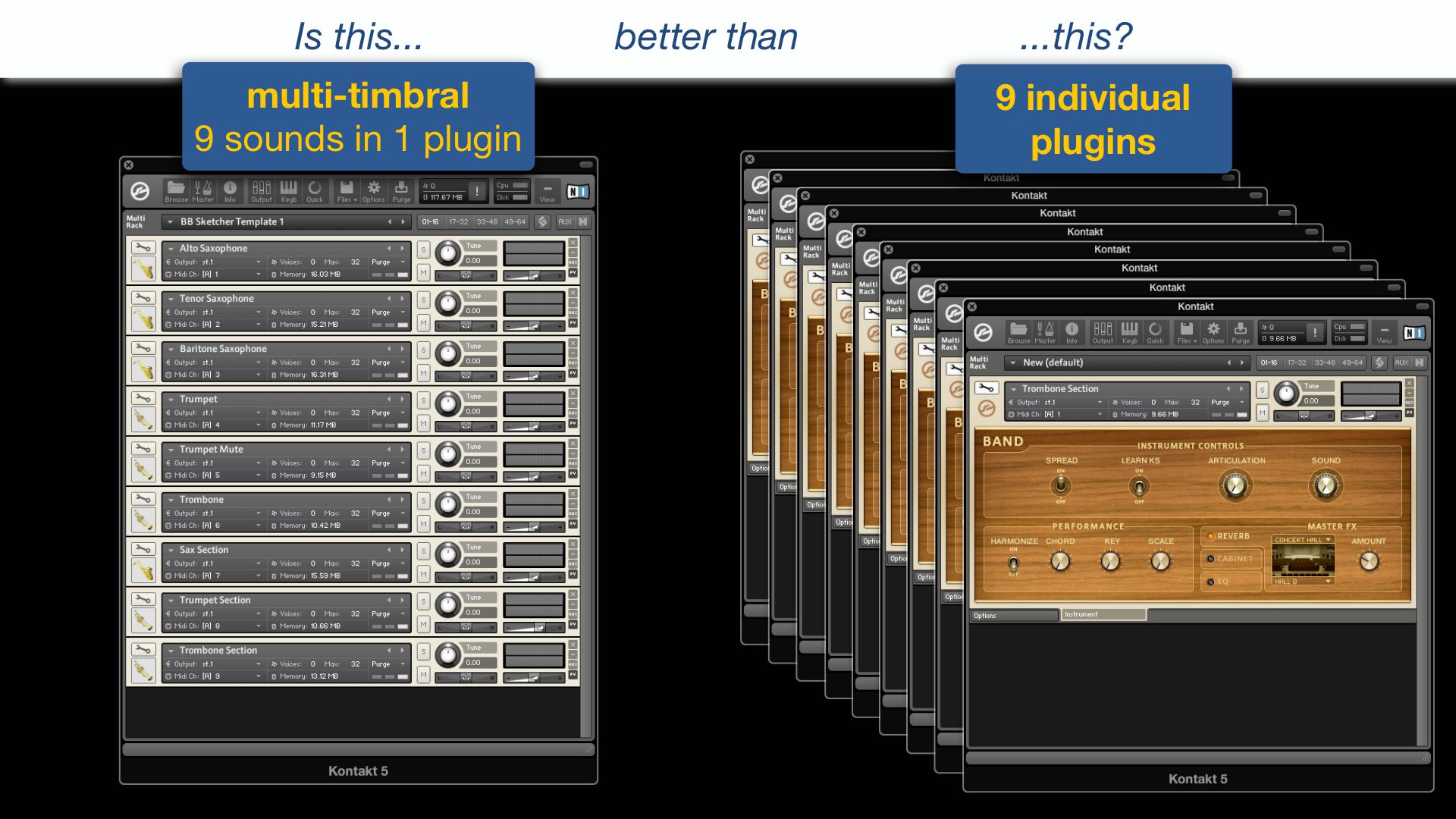

A multi-timbral, multi-output instance of Kontakt.

When you combine all of that decision-making with even more decisions about track layout, MIDI signal routing, plugin configuration, and the kinds of effects you want to have at-the-ready, what you end up with is pretty much the pat recipe for designing a template.

Or, it's a pat recipe for disappointment. Why? Well, with so many decisions to make, how do you know if you're going to get it right, especially after spending (typically) a considerable amount of time configuring things? Building a template based around even a single sample library is a time-consuming affair at best, and it's not unusual for the most well-thought-out-in-advance template to fall short in some way when it really counts—such as when you start a new project with a tight deadline. The last thing you need is to discover during crunch time that you're maxing out your computer's processing power as you attempt to create an ambitiously orchestrated soundtrack. It's one thing to build a template loaded up with, say, every sound available from a given orchestral sample library. But as you start to task your computer to play back increasingly dense orchestrations, you may well tax the available amount of CPU to the point where something fails. Computer performance gets unbearably sluggish, plugins drop notes, and things start to sound ugly—if not unfinished!

A Process of Discovery

Trial and error, and even trial by fire are the norm for template-building. And since everyone's system is different—computer model, amount of RAM, type and number of sample libraries being used, and so on—your actual recipe for building a template is almost always going to be… uniquely yours. Of course there are plenty of people you could turn to for advice, such as the entire Internet. But ultimately, how you decide to design and configure your template will depend on all of the above-mentioned variables.

Creating multi-timbral, multi-output instances does not necessarily save a meaningful amount of CPU, and makes template design quite complicated.

Help. Me. Please...

OK, no sweat! Here's some advice for first-time template builders! When you set out to build a template, especially a large orchestral template, don't start by loading up every single sound in a given library. Rather, build your template incrementally, starting with the woodwinds and working your way down to the strings. Or do it in the reverse or some other order. It's entirely up to you.

But the most important, most essential, most “there is no word to describe how important it is” aspect of these first steps is to actually write some music with your template as you're developing it. Even if you've just got the woodwind sounds of your library loaded up, go on and write a woodwind piece! See how your computer performs with just those sounds alone. While you're at it, experiment with buffer size, reducing it to be as small as possible to reduce playing latency but short of producing audio artifacts.

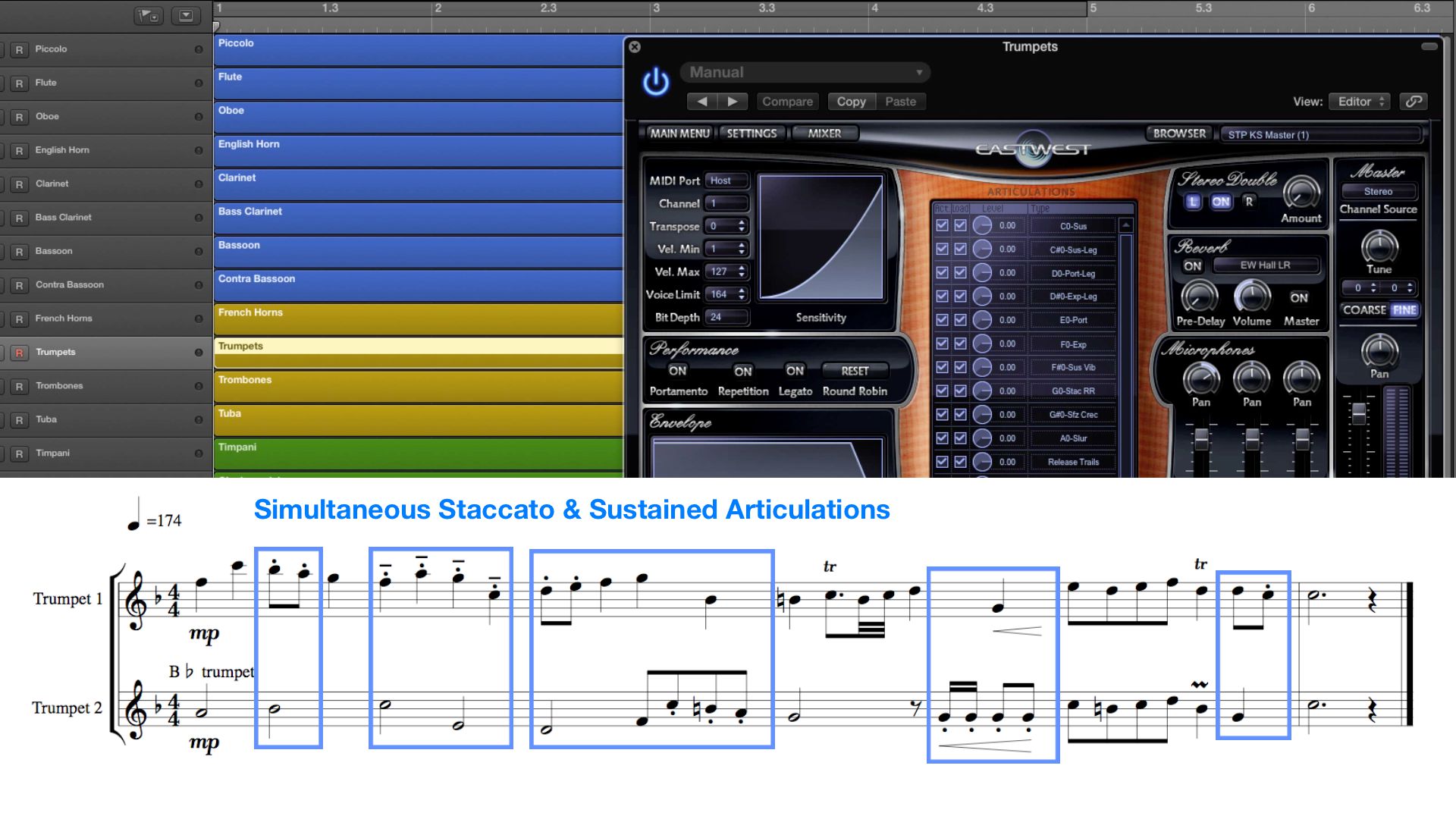

A situation where you'll need two instances of the same instrument, or, perhaps two libraries to play both parts.

By writing music with isolated sections, you'll likely realize if you haven't loaded up enough articulations to express your musical intentions, or perhaps you'll discover that there are certain sounds you'll probably never use (which you can then unload to save RAM and processing power).

Then incrementally add brass, percussion, strings, and so on, writing short pieces to test your system at each stage and see how your computer fairs with the ever-increasing need for CPU to run each new batch of sampler plugins.

Making music with an emerging template, as opposed to theorizing how it might work and going for it (especially when you're under pressure) is the best way to test your system. In the process you'll discover what your needs are, and even what compromises you may need to make in its design and sample content.

Back to the Question: Template, or Temporary?

Let's say you've arrived at a functional, feels-good, works-pretty-darn-well template, but then while working on a project you realize that it has certain shortcomings. These could range from, “I didn't give myself enough individual flute instances” to “I should duplicate my first violins to help make transitions between articulations smoother”. Should this occur, well, there's no need to cry over spilled milk (another thing “they” say apparently) at the effort you've already put in. Give yourself the latitude to recognize that when it comes to templates, change is OK. In fact, it may very well be inevitable. We all love the idea of “template” (as in “boilerplate”) but you may find that the reality is more akin to “temporary” as your requirements change over time. But don't let that put you off. We all have to start somewhere with our template designs, and an incremental approach—testing, experimenting, and writing music in the process—is the best way to get started.

You'll find everything you need to know to construct your own orchestral templates in The MIDI Orchestra—Designing Templates course.

Here's a preview video from Peter's course:

| Watch the entire course by Peter Schwartz at AskVideo here: |

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!