A lot of artists, producers, and engineers have gotten used to doing their own mixes (as opposed to calling in a mix specialist), and now, with the wide availability of software-based mastering tools, they've been trying their hand at that final stage as well. But mastering is really a different art than mixing—the focus is smaller, on little details, rather than big, creative gestures. It can take some time to re-adjust your ears to the kind of detail that needs to be addressed at that stage—I know it took me quite a while to get used to it, coming from mixing.

A mastering engineer is charged with making sure that the overall “sound” of the mix—in terms of tonal balance (EQ), density (compression), and overall level—is in the same ballpark as other commercial recordings. Everyone wants their song to stand out on the radio or in a playlist, but they don't want it to stand out in a negative way. A song shouldn't sound too much duller, or too much brighter, than others in that same genre; it shouldn't be too in-your-face (compressed) or too laid back, again, compared with other songs in that genre; and while it shouldn't be too much lower in overall level than other tunes, the quality of the mix shouldn't be sacrificed at the altar of loudness.

Sidestepping the Pitfalls

One of the key issues—for mastering in general, but especially for those just coming to it—is being able to maintain a reference to what the best commercially-mastered recordings sound like. Mastering tools, like multiband compressors and brickwall limiters, are powerful processors than can easily do as much harm as good. When any of us listen to a mix repeatedly, our ears become accustomed to the sound, even when there are flaws in it. And when we add processing, this leads to the tendency to overdo it—our ears get used to what we've done, and we want more of it—brighter, fatter, thicker, whatever—we don't notice when we've gone past the point where it's really too much. That mistake will eventually reveal itself in repeated listenings, especially by listeners with “fresh ears” (those hearing the mastered mix for this first time).

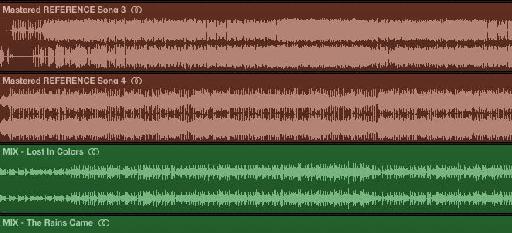

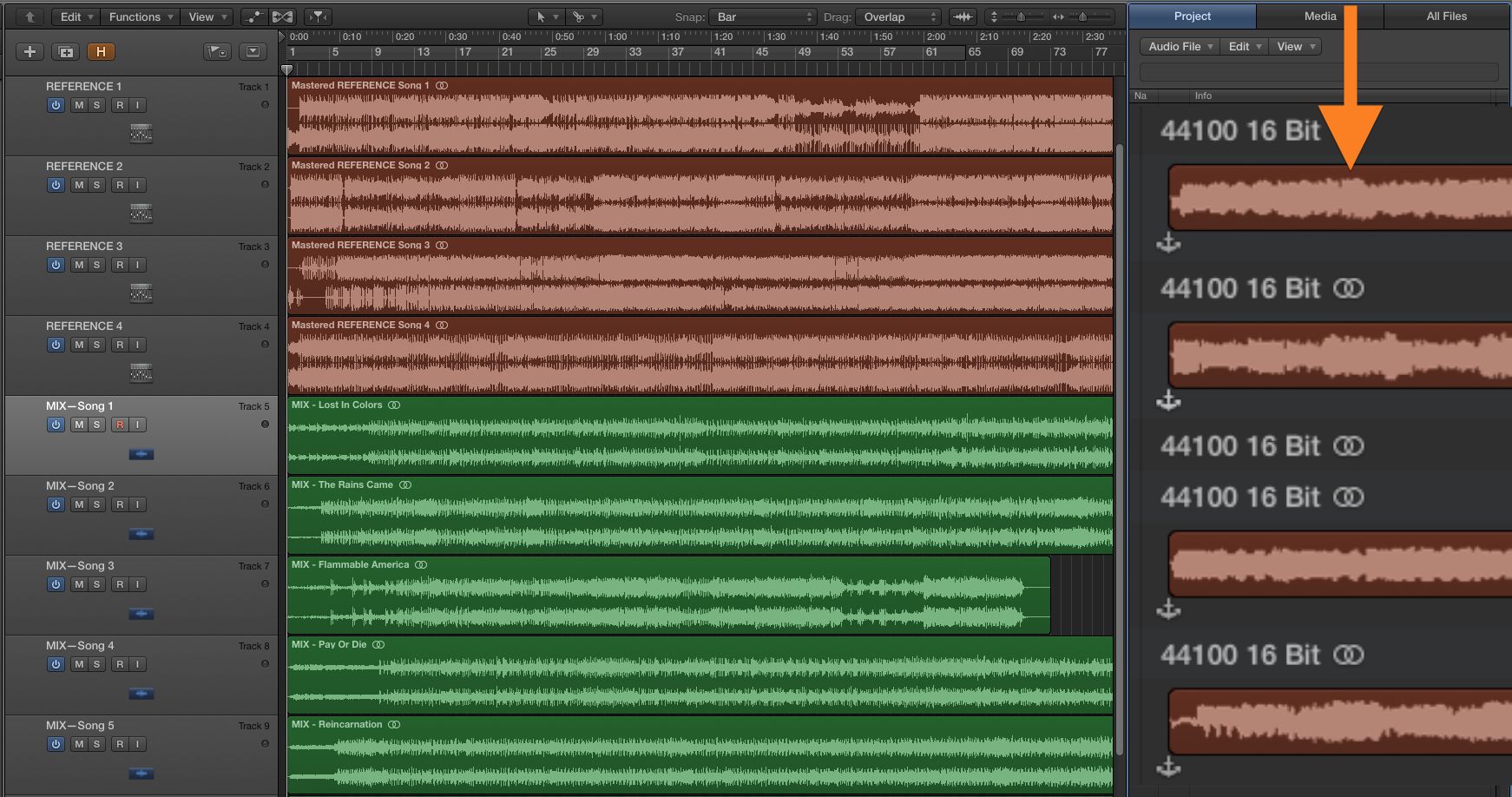

A mastering session with a collection of commercially-mastered reference tracks.

So how can we get around this? Well, one way is to keep a set of commercial reference tracks handy during mastering sessions. These should be loaded into the same DAW session as the mixes being mastered, on separate tracks. The mastering software should be applied at the track level, only to the new mixes, not on the main stereo output.

Mastering processors on the individual mix tracks.

Then the mastering tweaks being made can be A-B'd against these professionally-mastered commercial releases. If you play a song, pause, then play another song, your ears will forget the details of what the sound quality of the first one was, but if you A-B back & forth, quickly, on the fly, any significant differences—even subtle ones—will be immediately apparent. This approach really helped me to train my ears, when I first approached mastering. Eventually, with experience, your ears will start to maintain a decent internal reference, but at the outset, this is an excellent strategy for building up to that level.

Reference the Best

So how should these reference tracks be chosen and set up? Well, first off, they should be songs in the same or similar musical genre(s) of the songs you're going to be mastering. There should be several different songs in each relevant genre, all mixed and mastered by top engineers. They should be relatively current—they don't have to be this year's hits, but if they're more than 10–20 years old… well, mastering practices were quite different back then, and unless you're looking for a really retro sound, the overall sound will be too out of date to be used as a reference for modern production. Ideally, the reference tracks should all be full-quality LPCM (Linear PCM) format, not MP3, MP4, or AAC—the sound quality of files in those formats has been compromised to reduce the file size (for convenience), and they lack all the fullness and clarity of full-quality files. LPCM audio can be had from CDs (though 16-bit) or download sites that offer full-quality downloads (this currently does not include the iTunes store or most other popular sites).

A group of Linear PCM Reference tracks from CDs.

And it's important to note that they all won't—and shouldn't—have the exact same tonality. Pick any group of well-mastered commercial releases, and they'll all have slightly different tonal balances (some brighter, some darker), and different dynamic ranges (some more compressed, others less). But they'll all fall within the range of what artists, labels, and professional mastering engineers—and the listening public—have arrived at as the current standard. The key is not to try to slavishly match the balance and punch of any one particular recording, but to insure that your mastering efforts fall within that accepted, professional, range of sound quality. If your mastering efforts are consistently much brighter or duller, louder or softer, or denser, than all of the references, then that would suggest that you should take a step back, and maybe try a lighter hand at the controls.

The Importance of Level

When it comes to A-B comparisons, until you get to the final mastering stage—applying the brickwall limiting to crank up the level—you should adjust the levels of the reference tracks, by ear, to all be about the same as the level of the songs you're working on—even small level differences will negate the usefulness of the comparison process. When you are ready to limit and apply the final gain, set all the reference tracks' faders to unity gain (±0 dB on the fader).

Reference tracks: matched in level to the new songs for general processing (left:); at unity gain, for level reference at the final limiting stage (right).

And don't be afraid to not make your masters as loud as the loudest reference songs. The trend toward maximum level is already on the wane—if it sounds too squashed, back off. A final level a couple of dB lower than the loudest out there will still be fine, and may well preserve more of the snap & punch of the mix.

Utilizing reference tracks is just one aspect of the art of mastering, but it's a key part of the learning curve that'll set you on the road to the best masters possible!

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!