Most of the time an experienced engineer/producer will have no trouble dialing up a good vocal sound with the usual tools—EQ and compression (and a little reverb/ambience)—but every once in a while a troublesome vocal track needs a little more work. Here are a few suggestions for how to deal with such problem recordings.

Too Much Of A Good Thing

There are two ways a vocal track can be a problem recording—musically and technically. Typical musical issues include pitch and timing flaws, and nowadays there are many capable tools for dealing with those problems, but for this article I’m going to talk about the latter scenario—technical problems. That could include issues with uncontrolled dynamics and problematic recording technique, and I’ll talk about both of those problems.

I recently had occasion to work with a couple of tracks that offered those kinds of technical challenges; the singers were very good, with rich vocal tone, and the performances were excellent, with appropriate musical dynamics and interpretation, but listening to them against the mix revealed technical issues. The rich vocal tone may have been too much for the (unknown) mics—there was a bit of a honk in some parts, and occasionally the low end was a bit too heavy when heard in context of the overall arrangement; I suspected that at least one singer’s mic technique might have relied too much on live vocal performance techniques, with the singer “working the mic” aggressively.

This can help keep an uncompressed vocal in check dynamically in a live situation. But in the studio it can exacerbate potential issues like proximity effect—bass boost from being too close to the mic—and the tonal variations that may result from moving around too much on mic for a recording that will reveal those kinds of inconsistencies much more readily. Additionally, in both cases the musical dynamics that served the performance so well made the voice sit inconsistently in the mix, alternatively getting buried or sticking out way too much; in some sections particular words or phrases jumped out distractingly.

The Usual Suspects

Now these all sound like pretty typical vocal recording issues, and they are—nine times out of ten a standard application of compression will deal with those dynamic variations, and a little gentle EQ is usually enough to tame tonal problems like slight midrange honk or excess proximity. But sometimes those familiar issues are more resistant than usual to the standard processing choices, and then a little more work may be required to tame such a recording successfully.

Dynamic Swings

Most of the time a compressor is easily capable of controlling the kind of wide dynamic swings that make a track not sit consistently in the mix. Depending on the performance, either of two standard approaches would typically be taken: For a vocal with mostly consistent dynamics but occasional loud words or phrases that jump out, a higher threshold and ratio can be used to catch those sudden peaks, keeping them in line—something like a dbx-style compressor might be chosen for this.

For a performance that’s a little more inconsistent in terms of level, with sections that are both too loud and too soft (even though they may be musically appropriate), a lower threshold and ratio may be employed. This will provide some degree of compression on everything—loud and soft parts—but more on the louder parts, and the overall dynamic range will be subtly reduced, making the vocal sit more consistently in the mix. When done with a suitable compressor—maybe a classic optical compressor, like the LA-2A—a large amount of compression can often be applied without the vocal sounding overly squeezed.

But what if a vocal resists both of these approaches? Sometimes neither method seems to get the job done without choking the life out of the performance or introducing obvious compression artifacts (like pumping) which can be distracting in their own right. Well, the solution may be to use both—a high-threshold/ratio peak compressor/limiter to clamp down only on sudden loud notes, combined with a low-threshold/ratio compressor applied to the entire vocal range, subtly reducing overall dynamic range without trying to get that more gentle compression to clamp down on occasional peaks at the same time. In conjunction, two compressors addressing different aspects of the recording can often be more effective than asking too much of a single unit, and while it may take a little more fiddling to get the most effective combination of settings, the result can be worth it.

Gain Riding

On rare occasions, even the dual-compressor technique may not be able to tame a recording with very wide overall level swings or very strong occasional peaks, or both. On those rare occasions, it may be necessary to go old-school, and do a little gain-riding. Gain riding refers to the manual adjustment of changing levels, like what live engineers do with a hand on the vocal fader. Once again, on its own this may not solve every problem—lots of sudden level jumps will likely defy any manual attempt at realtime level control—but often a little gain riding applied prior to compression may be able to address the most extreme level variations, making it possible to then apply a moderate amount of compression that will get the rest of the job done without introducing artifacts of its own.

In a mix situation, there are several ways to implement gain riding, whether on its own or in conjunction with compression. Obviously, automation would be utilized to commit any manual fader moves to the mix, but there’s more than one way to go about that. Standard track automation could be employed—depending on the performance, the engineer could ride the vocal fader in realtime, recording the automation on the fly, or draw in the level variations graphically, following the visual peaks and dips in the waveform as a guide to when and how much level adjustment should be added throughout the track.

This can work well, but it can also be tedious and time-consuming, especially in comparison to the relative efficiency of setting up a compressor for level control. And standard track automation of the channel fader would follow any compressor used on the track, which—depending on settings—might still exhibit pumping or other artifacts on the still-highly-dynamic signal hitting its threshold.

Clip/Region Gain

Another way to apply and automate gain riding would be to apply it prior to compression, and that could be done via the DAW’s clip/region gain feature. Whatever name it goes by, clip or region gain is a level control tied to the clips/regions themselves, which precedes any processing (compression) in the inserts. Depending on how the feature is implemented this can sometimes be a more effective alternative than channel fader gain-riding/automation, at least somewhat smoothing out dynamic variations before the signal hits a compressor.

The simplest version of this feature offers a single level adjustment for each region, which means that longer regions or tracks with lots of quick level swings might need to be heavily edited—cut up into appropriate smaller regions, each with an appropriate gain setting.

A more full-featured version—like Pro Tools’ Clip Gain feature—might offer continuous clip gain, which can be drawn in visually following the waveform, just like track automation. This would make it easier and more efficient to apply gain riding to a dynamic recording prior to hitting it with compression—it wouldn’t be necessary to track every slight dynamic swing, simply dialing the level up and down in broader strokes would allow any compression that follows to be applied more gently, achieving both control and a smoother, more subtle dynamic character.

Tonal Tweaks

For tonal issues that seem to be resistant to the subtle EQ (a few dB at most here and there) that’s usually applied to vocals, sometimes it may be necessary to shake off the typical self-imposed restraint that most experienced engineers stick to when EQing vocals, and dial up stronger dollops of EQ by ear—this could be the ticket for correcting excessive proximity or vocal honk. However, some tonal issues might be a little more difficult to remedy—if undesirable tonal variations are the result of room issues like reflections, or the comb filtering that can occur in a smaller spaces like an under-damped vocal booth, they may be the result of many smaller peaks and dips in response, a ragged response which may not be dealt with sufficiently by typical broader EQ curves.

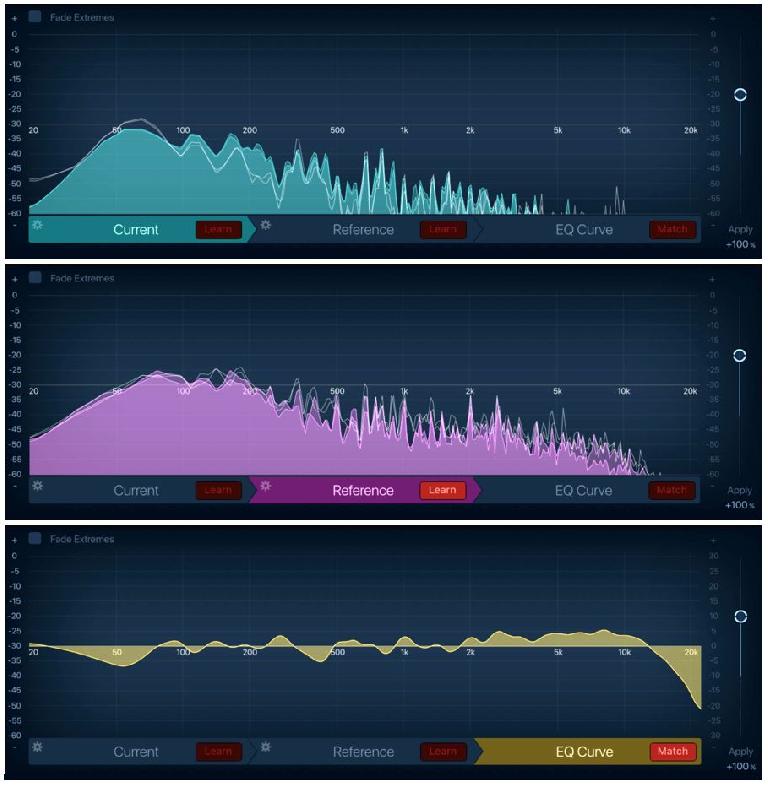

One approach that might be helpful would involve the use of a matching EQ, a specialized tool available with some DAWs (Logic) and plug-in suites (iZotope). This analyzes the tonal balance of two recordings—a reference track with the desired tonal balance—in this case simply a smoother overall frequency balance—and the problem track that needs to be EQ’d. If another recording of a particular singer is available—one that has a better, more appropriate tonal quality—then that recording could be used as a reference, using the matching EQ to apply a similar tonal balance to the problem track. Most matching EQs dial up a complex curve that will try to match many small frequency variations, but also let the user smooth out that curve by ear, until the best tonal balance is found.

Since in this scenario you wouldn’t actually need to precisely match the reference tone—just use it as a guideline for the EQ to calculate the best frequencies and gain settings to apply—even if a suitable recording of the same singer isn’t available, a recording of a singer with a similar vocal quality might even do as a reference for this application. Of course, more experienced engineers would probably only turn to this kind of approach as a last-ditch effort, preferring to rely on their ears and experience, but it could conceivably help.

Final Word

With the problem vocal tracks I mentioned earlier (that suggested this article to me), I dealt with these kinds of issues with dual compression in one case, and a combination of gain riding with region gain and a single gentler compressor in the other. For tonal issues (proximity and honk) I dialed up as much as 6 or 7 dB of boost and cut—a crazy large amount of EQ for me to apply to a vocal—but despite my ingrained reservations about making the voice sound too “canned” or too processed, listening back to the mixes the next day the vocal tone seemed fine—a little EQ automation for a stray honk here and there, and I was satisfied with the results.

So when you come across a problem vocal track, and you find that your usual approach to EQ and compression isn’t cutting it, don't be afraid to get a little more creative. But when applying more processing to a track than you normally would, always be sure to periodically A/B the track with and without that processing, and even against other similar tracks/mixes, just to make sure you haven’t gotten too far off base.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!