Most people in the music/audio industries nowadays are well aware of the need to protect their hearing, but every once in a while it can’t hurt to have a little reminder of both the dangers and the various ways to guard against them.

Ear We Go

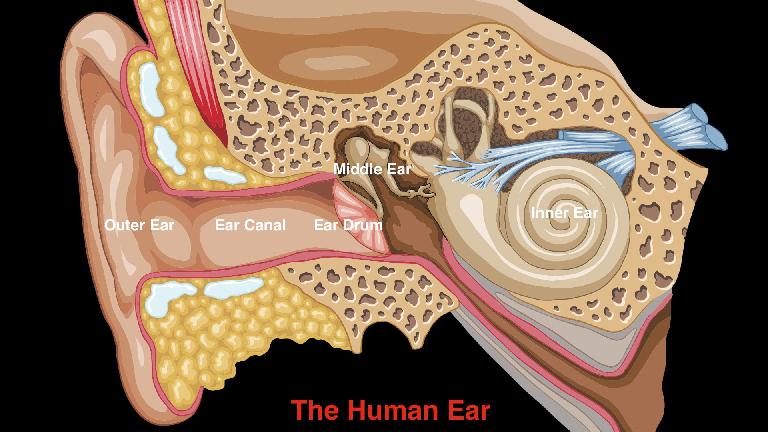

Our ears really are little mechanical wonders, with sound waves passing through various media within the ear on their way to the nerve endings that carry them to our brains, which ultimately make sense of it all.

Air pressure variations initially make their way through the ear canal to the ear drum, which vibrates sympathetically; these vibrations are then transmitted mechanically to the middle ear - three little bones. The bones of the middle ear do double duty - they transmit the vibrations to the inner ear, and at the same time they serve as the first line of protection against hearing damage - if a sound wave’s vibrations are too intense, the bones of the middle ear limit the strength of the vibrations passed along to the delicate mechanisms of the inner ear, acting as a compressor. Of course, this is not a fail-safe by any means, but it is at least one small layer of protection. In the inner ear, the audio wave is sent through a fluid-filled tube - the cochlea - where it disturbs tiny nerve endings - hair cells called cilia. These transmit the disturbances through the auditory nerves to the brain, and...voila, we hear.

What’s That Ringing?

Hearing damage from exposure to sound can occur when the some of the cilia are damaged, and can no longer respond to sound waves. This kind of hearing damage can manifest itself in two ways: Temporary Threshold Shift and Permanent Threshold Shift. Obviously, the ear can recover from Temporary Threshold Shifts, while a Permanent Threshold Shift indicates an unrecoverable loss of hearing, to some degree.

Symptoms are the same in ether case: a loss of sensitivity, initially in the range where our ears are most sensitive - around 4kHz - and possibly a ringing in one or both ears. The loss of sensitivity in that particular frequency range can show itself as a loss of clarity and intelligibility - this can be subtle enough to largely go unnoticed, or obvious enough to make the person aware of a change in their hearing response. The ringing is called Tinnitus - it also can be subtle enough to not be heard unless the background level in the room is unusually quiet - people often first notice it when they’re trying to get to sleep - or loud enough to make its presence known under any environmental conditions.

If it’s a Temporary Threshold Shift, these symptoms will go away, usually after about a day or so - assuming the individual gives their ears a rest from any further exposure to even moderately loud sound during that period. But if it’s a Permanent Threshold Shift, the symptoms, naturally, will persist, and often grow worse over time, especially if exposure to similar levels of sound continues. The ringing in particular - the Tinnitus - can sometimes be severe enough to become somewhat debilitating for certain people, requiring medical treatment, though currently there is no definitive cure.

Who’s At Risk

So, among musicians and audio industry people, who’s at risk, and under what conditions? Well, the short answer is that everybody is potentially at risk, though some situations are clearly more prone to causing hearing damage than others. Given the sound pressure levels of even acoustic instruments - let alone amplified ones - any musicians in close proximity to loud music-makers on a regular basis should consider their ears.

Drummers are particularly prone to hearing damage, and not just from the drums with the strongest impact transients, like snare; cymbals have strong frequencies in the ear’s most sensitive range, where damage usually first occurs, and they’re typically mounted more or less at ear level. The guitarist who likes to stand right in front of his cranked amp is subjecting himself to another kind of sound that’s particularly strong in that dangerous frequency range. And musicians who play quiet instruments are not necessarily immune, either - the orchestral flutist may not generate enough level to put her hearing at risk, but the trumpet or trombone player who sits directly behind her in the orchestra, with his instrument pointing right at her head, certainly does - in fact, he’s probably at less risk given the specific directionality of most brass instruments. And of course, loud speaker playback can be a potential hazard to anyone, especially those directly in the line of fire.

It’s Not Just The dB’s

Everyone knows that it’s exposure to louder sound levels that’s most likely to cause hearing damage, but people are often not sure exactly how loud things need to be before they should start worrying. Unfortunately, there’s no short answer, because the culprit is not just level itself, but level in combination with exposure - the amount of time the ears are subjected to sound loud enough to cause problems.

Naturally, sudden loud sounds, like gunshots or up-close fireworks, that produce a sound pressure level that approaches the Threshold of Pain, are must-avoids - even a one-time exposure, if it’s severe enough, can cause permanent damage. But in more typical situations for musicians and studio people, the sound is not that loud or that sudden - instead it’s fairly continuous, and that’s where the real danger lies.

Keeping Time In Mind

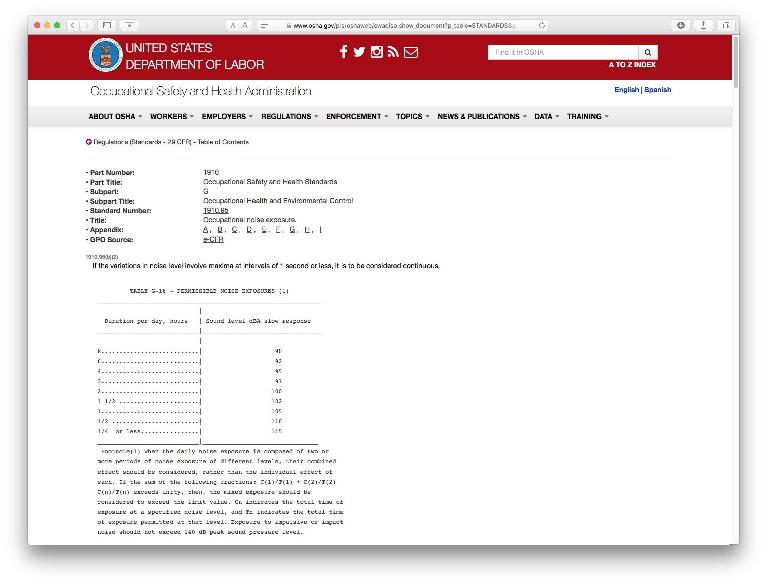

Above a certain (approximate) level, the louder the sound is, in dBspl, the less time our ears can handle exposure to it before they might conceivably succumb to hearing damage. Any sound above around 85-90 dBspl, if pumped into the ears long enough, has at least some potential for trouble, and long stretches of music at 90-100 dBspl can easily bring on at least some degree of Temporary Threshold Shift. For workers who are exposed to loud sound levels on the job, OSHA - the Occupational Safety and Health Administration - has regulations for limiting the length of continuous exposure (without a break) to continuous sound at various levels; these are readily available on their website.

However, OSHA’s guidelines apply more to really continuous sound, a like a factory worker’s exposure to the constant loud thrum of a turbine, for example. Music is not that continuous, or that steady in level (though some modern mixes with their hyper-compression may be approaching it), so the OSHA rules don’t translate directly to stage or studio. But the principle still holds: musicians and studio personnel should take frequent breaks, ideally, at least 15 minutes or so every couple of hours, and not just to protect their hearing - this is a good idea for other reasons as well, both technical and creative.

A common recommendation for studio work is to monitor at an average level of around 83dBspl, which should allow for longer stretches without putting the ears at risk, but many people like to work at levels closer to around 90dBspl or so, and in that case, breaks are definitely in order.

When monitoring on headphones, frequent breaks should always be taken - the level in headphones, without the low-end vibration from speakers, can be deceptively loud, and many phones have a lot of presence, again, right in that danger zone around 3-4 kHz (this is especially the case with earbuds).

Plug It Up

Of course, sometimes you have no control over either the sound pressure level or the length of exposure. Musicians on tour, or studio assistants who work for the kind of producer who’s fond of all-night sessions and never seems to want to step away may find that they’re exposed to potentially risky levels of sound as an unavoidable part of their job. When that’s the case, some thought should be given to wearing ear protection. Now, I know a lot of people hate to jam things in their ears - I’m one of them! But if you go home with your ears ringing every night, you’d better think about taking some action before one day that ringing simply doesn’t stop.

If you do decide that some kind of hearing protection is warranted, don’t resort to stuffing wads of tissue paper or napkins in your ears - that’s pretty ineffective. And those cheap yellow or pink foam ear plugs you get in the pharmacy may help a little in the subway, but they’ll most likely muffle the sound far too much to be of use if music and audio is your business. Instead, you’ll want to look into the kind of high-end hearing protection that’s often custom-molded to your ears - these can be optimized for the individual user, and are designed to at least try to maintain as flat a frequency response as possible, which is critical for those in the audio business.

Keep Your Ear To The Ground

Most importantly, no one who values their hearing can afford to ignore any symptoms of potential hearing damage, no matter how mild they may seem. For musicians and audio folks, our hearing is our business, and it deserves to be protected as diligently as possible - to paraphrase the old cliché, you only get one pair of ears.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

In my ears that is to high. I always take my level meter an place it right in front of my. Simply put it on the mixer. The average level never extend 65 dBspl.

That works for me.

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!