Welcome to part three of this series on utilizing modes for improvisation. So far, I’ve given you an overview of what the modes are, and last month I shared some tips for utilizing the major modes. Today, I’ll be giving you some inspiration and techniques to utilize the minor sounding modes in your music.

Which Ones Are Minor Again?

For a mode to be classified as ‘minor-like’ it’s going to have to have a flatted third. This will make it effective over minor harmonies. The four modes that have a minor third in them are Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian, and Locrian. Today, we’ll take a look at Aeolian and Dorian.

Aeolian is Minor

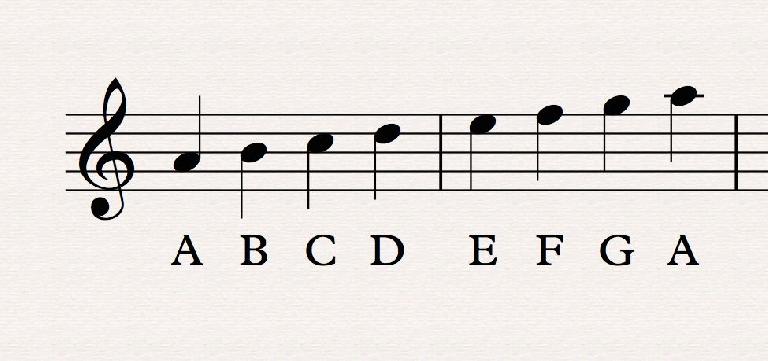

Aeolian mode isn’t just minor-like, it’s natural minor! The aeolian mode utilizes the exact notes of the natural minor scale, and you can also build it by taking any major key and building a scale on the sixth note of it. If you want to find the A aeolian scale, simply play a C major scale and start on C. Or play natural minor (major scale with flat 3, flat 6, flat 7).

Aeolian mode works well over just about any minor tonality. If you’re using an A minor chord, you can make a safe bet that A aeolian will work to build melodies and solos over it. When you’re looking to expand your tonal palette beyond the simple minor scale, it isn’t the current chord you typically have to worry about clashing, it’s the previous or next chord that could cause a problem.

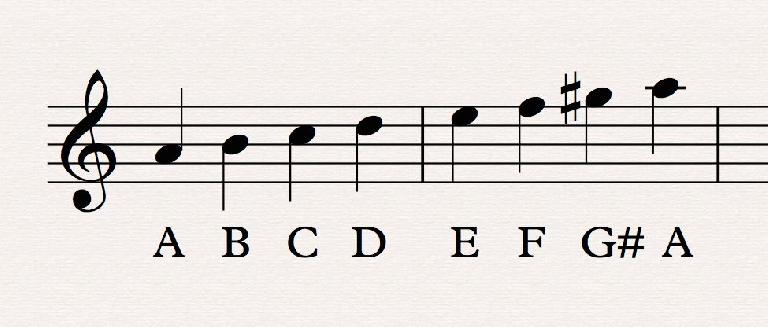

Take the following case in point. You have an A minor chord, so you write a melody with A-B-C-D-E-F-G over it. Your next chord is an E major chord, a major 5 chord. That G natural doesn’t sound so great over it any more, so that’s a case where you may want to consider a different scale, like the harmonic minor scale.

You may even want to consider using that harmonic minor scale over the A minor chord because the implied harmony coming up dictates it! As always, use your ear to guide you. The half step is an incredibly powerful interval, and utilizing it to give your melody some ‘pull’ in a certain direction can really make the melody stand out.

Dorian is the Next Step

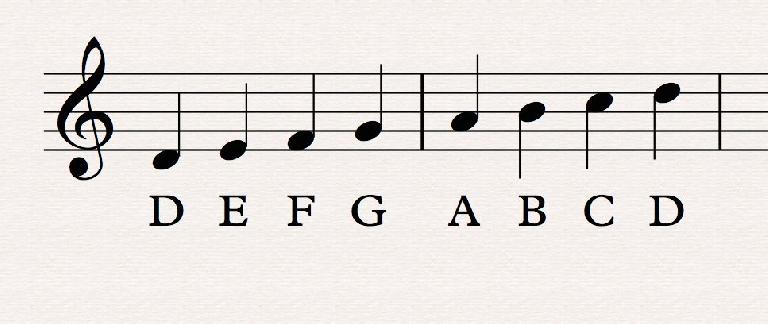

Dorian mode is natural minor with a raised 6th note (or a major scale with a flatted 3rd and a flatted 7th). If you build a scale on the second degree of any key you’re working in, you’ll get Dorian. Let’s go back to C major. If you play a C major scale, but start it on the 2nd degree of C major (D) you’ll get D dorian.

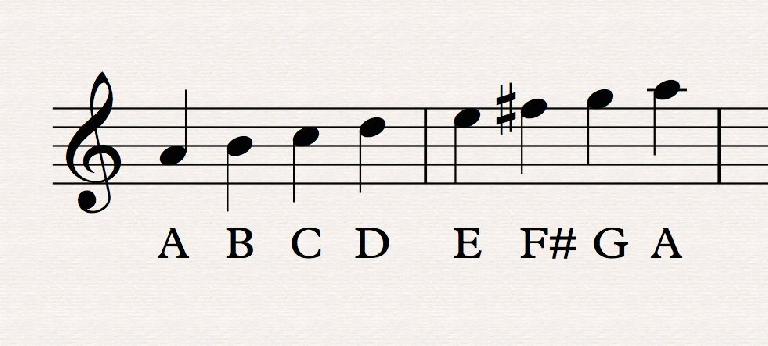

Dorian is a great scale to start with on your journey away from simple major/minor. The raised 6th note will separate it from the ‘minor sound’ and make it a little more jazzy. It will also work well any time you have a minor 1 chord and a major 4 chord. Let’s say, for example, you’re playing a song in A minor that has an A minor chord followed by a D chord. Using A dorian would be a good choice, because playing an A minor scale and raising the 6th will give you an F#. That F# just so happens to be the note that makes a D major chord sound major! It works both ways, too! If you’re writing a song, instead of sticking with all minor chords why not try inserting a major 4 chord and allow yourself to use a dorian tonality?

When you’re looking at the above scale, do you see it as A dorian? Perhaps you view it as G major? You can really think of it both ways. Of course, naturally we want to lean towards A dorian since it starts on the note A, but without a functional harmony beneath it you really can’t tell! After all, who said that you need to always start on the tonic note (the first note) when you’re building a scale during a solo? As you advance in improvising and writing melodies, you’ll likely start to gravitate away from starting every single phrase you write on the tonic!

Check out So What by Miles Davis, or perhaps Evil Ways by Santana if you’re not really into jazz as much. These are both great examples of the use of Dorian.

In the case of So What, you’ve got the dorian tonality baked into the melody. Listen to that bass melody in D minor utilizing a B natural (the raised 6th). The answering chords go from a major 4 chord (G) to a minor 1 chord (Dm) which is the ‘dead giveaway’. When listening to Evil Ways, you’ll notice that the singer avoids the 6th note of the scale completely, which makes it stand out all the more within the chord if you ask me! The two main chords of Evil Ways are G minor and C major, a minor 1 chord and major 4 chord respectively. When the band hits that major 4 chord, it really stands out!

Putting it into Practice

Music theorists are often divided into 2 camps. Some feel that you should learn the modes based on their ‘home note’. In other words, learn that A dorian has a minor third, minor 7th, and major 6th. Others will state that you should learn that A dorian is ‘related’ to G major, and that if you build a G major scale on A, you’ll get A dorian.

I have always felt that knowledge of both is important. I’ll practice my dorian scales thinking of the home note tonality, and then I’ll practice the dorian scales thinking about the relative home note tonality. I think that knowledge of both will make you a better composer and improviser—ready to utilize a large palette of scales at any time!

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!