This year marks an important milestone in music technology: the 30th anniversary of the introduction of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) to the musical marketplace. For the below-20 crowd, it might be hard to imagine life without MIDI and all of the creative flexibility it offers. But there was indeed a time when creating a multi-track production meant, for the most part, performing parts live to tape one track at a time.

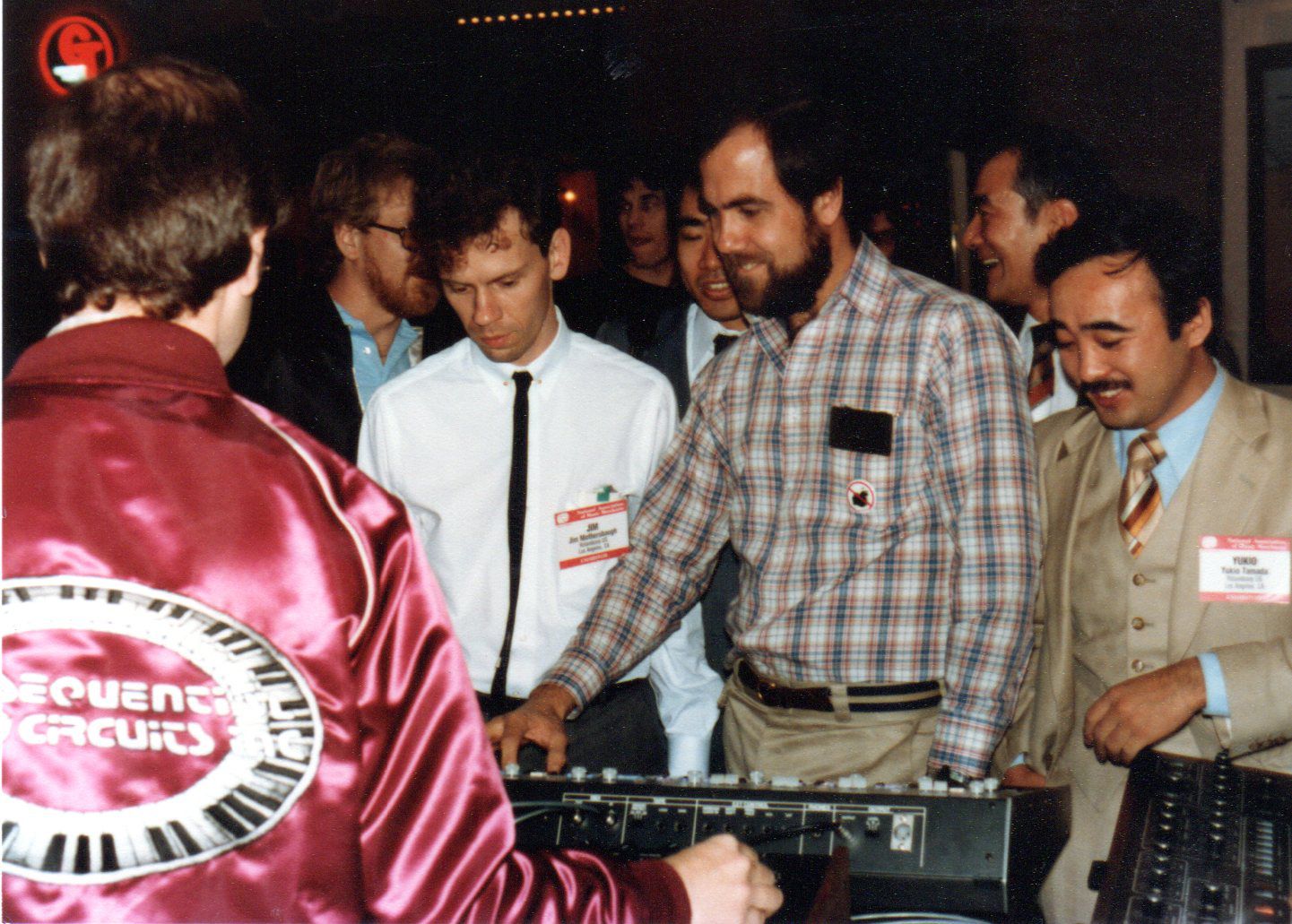

In a long-overdue act of recognition, the Recording Academy awarded MIDI's inventors Dave Smith (Sequential Circuits, Dave Smith Instruments) and Ikutaro Kakehashi (founder of Roland) a Technical Grammy in February. Considering that MIDI made its foothold in music production only a few short years after MIDI devices became commonplace, it's surprising that it took three decades for MIDI's architects to be acknowledged with the music business's highest honor. But as they say, “better late than never!”

Click here to read a press release from Roland Corporation

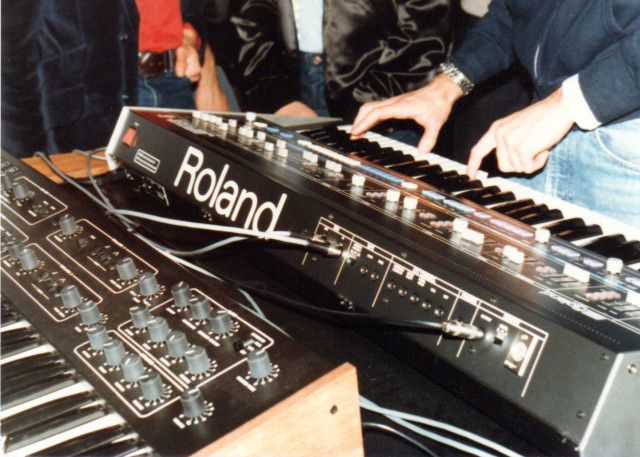

Photo from the first public demonstration of MIDI at the 1983 NAMM show. Seen here are a Roland Jupiter 6 and a Sequential Circuits Prophet 600 connected via MIDI cables. Photo courtesy of Dave Smith.

Life After MIDI

The first musical devices to sport MIDI jacks were polyphonic synthesizers, specifically, Sequential Circuit's Prophet 600 and Roland's Jupiter 6. For the first time, musicians could easily connect two polyphonic synths with a single cable, play the keyboard from one, and trigger the sounds from both.

Back panels of the Prophet 600 and Jupiter 6 showing MIDI In and Out jacks. (Photographs courtesy PerfectCircuitAudio.com)

Life Way Before MIDI

Now, layering two or more sounds from a single keyboard wasn't itself a new concept; mechanical linkages found in the earliest multi-ranked pipe organs let a performer couple multiple sounds on each key. But such capability wouldn't be realized even in the more contemporary milieu of monophonic (single voice) synths of the 1960's to early 1980's. While it was an easy affair for a synthesist to connect control voltage and gate signals between two synths of the same brand or manufacturer, connecting dissimilar synths was problematic. There was no standardization between brands of the electrical specs for these signals, and without specially built circuits or expensive adapter boxes, it was impossible to connect, for example, a Korg MS20 and a Minimoog.

Even when such connections were facilitated, monophonic sound layering – useful as it was – paled in the imagination compared to the notion of layering the sound of polyphonic synthesizers, and long-remained a pipe dream.

Back panel of the Minimoog and its “S-Trig” gate connector which was incompatible both in form (spade lugs) and its electrical characteristics, requiring special circuitry to connect to other commercially produced synths of the day. (Photo courtesy PerfectCircuitAudio.com)

In this never-before published photo, Dave Smith demonstrates MIDI at NAMM, 1983. Looking on are Yukio Tamada of Roland (right) and Jim Mothersbaugh (left). (Photo courtesy Dave Smith.)

The first polyphonic synthesizers (Prophet 5, Polysix, OBX, to name three) were technological milestones in their own right but no more compatible in terms of connectivity. But once MIDI arrived on the scene and manufacturers began to incorporate it into their products, playing one synth from another became commonplace, and today this capability – and much more – is easily taken for granted.

The Oberheim OB-X: one of the first polyphonic synthesizers. (Photo courtesy PerfectCircuitAudio.com)

Evidence of a MIDI retrofit installed in this unit. (Photo courtesy PerfectCircuitAudio.com)

MIDI: A Solution of Elegance

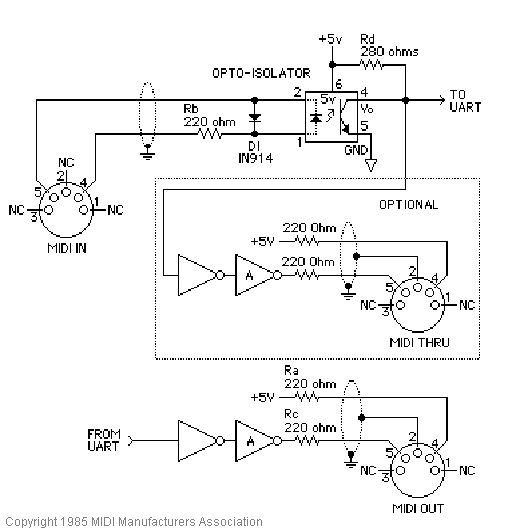

The success and longevity of MIDI has as much to do with the cooperation of musical instrument firms agreeing early-on to adopt MIDI as a standard, as is the simplicity and elegance of the MIDI system itself, starting with the familiar 5-pin DIN connectors and the relatively simple circuitry which transmits and receives MIDI messages.

Circuitry for driving MIDI inputs and outputs. Image courtesy the MIDI Manufacturer's Association (www.midi.org)

Thankfully, it's not necessary to have an electrical engineer's understanding of the MIDI circuitry itself to make music with MIDI, though when it comes to connecting MIDI devices, the principle of “outputs go to inputs” applies: MIDI messages generated from the device you're playing (the transmitter) are fed to the MIDI input of the device being played (the receiver).

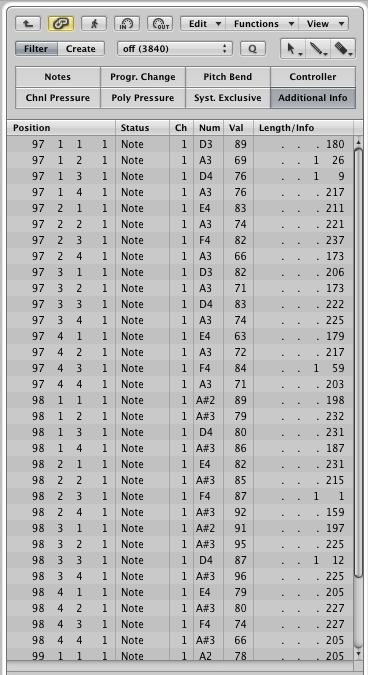

Screenshot from MacProVideo's MIDI 101: MIDI Demystified.

MIDI Messages

Then there is the system of the messages themselves, and to get the most out of your MIDI devices (as well as for troubleshooting purposes) it's important to understand something about the kinds of information contained in them. Fortunately, the concept of what these messages are all about is simplicity itself: MIDI messages contain information about each action you perform on a MIDI controller. For example, when you press a key, a Note On message is transmitted saying which key was played and how hard you played it. When you release a key, a Note Off message says that you released that specific key.

Similarly, when you step on the sustain pedal, a Control Change message, or “CC” is generated saying that you pressed it down, and another is sent when you release it.

Yes, it's really that simple: each individual action you perform on a controller is translated into a MIDI message.

MIDI Sequencers

MIDI messages are generally referred to as “events”. And when you play a passage on a keyboard, you are performing a series of actions that result in a sequence of Note On and Note Off messages. Thus, when you record MIDI, you are recording the “sequence of events” generated from your controller. And now you know why the MIDI-recording part of a DAW is referred to as a sequencer!

MIDI and its Relation to Sound

Probably the most important thing to realize is that MIDI messages are not sound messages. In fact, MIDI has nothing to do with sound itself. Rather, MIDI devices and virtual instruments produce sound in response to MIDI messages.

Tweakability

Having a good working knowledge of the information contained in MIDI messages becomes important when you want to edit aspects of your recorded performance. For example, you'd want to be aware that velocity information is contained in each Note On message, and that its value can range from 1 – 127. So if you played a few notes too hard or too soft, you can use your sequencer's editing facilities to alter those values, perfecting your performance after-the-fact.

A typical MIDI Event List as found in most DAWs, displaying recorded MIDI events. This list, from Logic, shows details of recorded Note On events.

MIDI Channels

Another important aspect of MIDI messages is the MIDI channel, a number ranging from 1 – 16 which is embedded in the most commonly encountered MIDI messages (notes, CC's pitch bend, aftertouch, and others). Selecting a particular channel number for a stream of MIDI messages (the “transmit channel”) lets you specifically target a MIDI device or plug-in to react to those messages, meaning this: if the channel of the transmitting device (i.e., your controller) and your destination instrument (the receiver) are set to matching MIDI channels, the receiver will react to the messages; if the channel numbers don't match, they won't.

In Closing…

Much more can be written about MIDI, how it works, and its strengths and weaknesses. But reading about it is rather dull compared to the entertainment value you'll find in watching my video tutorial, MIDI 101: MIDI Demystified.

In closing, I would like to offer my thanks to Messrs Smith and Kakehashi for their wonderful invention which, 30 years later, I can't imagine living without.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2013/04/11/one-of-techs-most-successful-inventors-never-made-a-cent/

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!