Major releases from all over the world differ from each other in their perceived loudness, with labels and producers still bashing their headroom against the ceiling trying to get the “most” out of their releases. The loudness wars are over but dance land is still a digital dust storm. For broadcast, the problem of some programmes being louder than others has largely been rectified by the implementation out of an industry wide target loudness of -23 LUFS.

(If LUFS and LU’s still confuse you, catch up here: https://ask.audio/articles/demystifying-the-confusion-around-loudness-metering-levels)

But where does that leave EDM producers and independent musicians releasing their own music online? What loudness levels should we aim for? Short answer: A target loudness of -16 LUFS with peaks no higher than -1 dB TP (true peak) is the AES recommendation for streaming content. (Technical Document AES TD1004.1.15-10)

A target loudness of -12 to -9 LUFS would bring you up to traditional CD levels, but -9 LUFS kind of defeats the point of caring about levels, and -12 LUFS is arguably still too loud.

As we shall see, there are technical reasons for aiming lower than these two targets.

Long Answer

Target Loudness depends on the destination platform. The EBU R 128 recommendation is specific to the broadcast platform, and is not a standard for music production yet.

- - 23 LUFS as a target level is primarily for broadcast content.

- - 9 LUFS is generally the target for “old school” CD mastering.

There are two issues with these targets for modern music makers. First, - 23 LUFS falls below the AES recommended minimum target level of -20 LUFS for streaming. This is because current portable media devices (especially those adhering to European regulations) do not have sufficient gain to hear these levels in day to day situations like commuting. Second, who listens to CDs anymore?

Seriously though, - 9 LUFS might be loud enough to (theoretically) compete on the dancefloor, but it’s much louder than the loudness levels used by at least three major streaming services online:

- iTunes (Soundcheck and Radio): -16 LUFS

- Youtube: -13 LUFS

- Spotify: -12 LUFS

So, why is this an issue? Streaming through, or from, a mobile device is how most of your audience will engage with your music outside of Live/DJ sets, so optimising for streaming makes sense. Crucially, it is more beneficial to have a dynamic track turned up than to have a loud, compressed track turned down, so mixing and mastering to -9 LUFS for online audio is not a great idea. It will get turned down, converted along the way, and possibly hit limiters (of questionable fidelity) on those systems, further degrading your sound. So if - 23 LUFS is too soft, - 9 LUFS is too loud, and -12 LUFS is outside of the AES recommendations, what should we aim for with dance music?

Target Levels for EDM

Club land is still the wild west when it comes to loudness unfortunately. For example, Richie Hawtin’s “From my mind to yours” (2015) seems to hover around -10 LUFS per track, Claude Van Stroke on Dirty Bird is a whopping - 6 LUFS per track, and Deadmau5’s seminal track “Strobe” is a surprisingly conservative -12 LUFS. -16 LUFS should still be your final target though, and have the DJs level match via gain on the mixer in the club.

Remember, Loudness normalisation does not replace mixing and mastering. It will not fix frequency issues or balance issues – a weak mix will remain weak, and over-compressed, brick-wall-limited audio will simply be turned down.

Gain Staging and Issues with RMS and Peak Measurements

How you gain stage before loudness normalisation is entirely up to you, but mixing to around -23 LUFS is good practice. Wait, why not mix with familiar peak and RMS readings, and loudness normalise at the end? On the surface a -23 LUFS pink noise signal measures just shy of -23 dB RMS, but two music tracks measuring the same RMS values may not necessarily have the same perceived loudness. RMS does not take into account the psychoacoustic nature of apparent loudness as heard by the human ear, but the Integrated loudness measurement specifically does.

Furthermore some RMS meters average rather than sum input giving you an inaccurate reading of up to -3 dB or more. Sample peak targets are obsolete, traditional peak-sample meters cannot measure intersample (true) peaks which can lead to problems further down the line when converting audio to lossy formats like MP3.

Notes on Monitoring

Compared to old school “mastered-to-0.1dB-peaks” and RMS levels between -12 to - 6 dB (depending on material), mixing around -24 LUFS can seem a tad low. It is counterintuitive at first, but at these levels you are opening up serious headroom for your peaks, and this affects perceived signal quality. A recording with a high (True) Peak-to-Loudness ratio (PLR) is often perceived as clearer and less fatiguing than one that has been excessively peak-limited.

If things are sounding too quiet in your studio, turn up your monitors not your mix! You should also consider calibrating your studio monitors so that you have a known, fixed reference level while you work – https://ask.audio/articles/why-you-should-calibrate-your-studio-monitor-speakers

Finally, while it’s good practice to keep an eye on your meters while mixing, ears and music come first, so don’t forget to listen!

Other Numbers

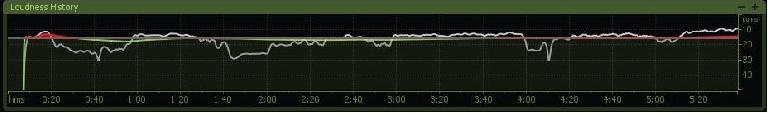

The final -16 LUFS target is an Integrated average (1) of the whole track (measured from beginning to end). This means that some parts of the song can be momentarily louder or softer than the target level without affecting the overall measurement.

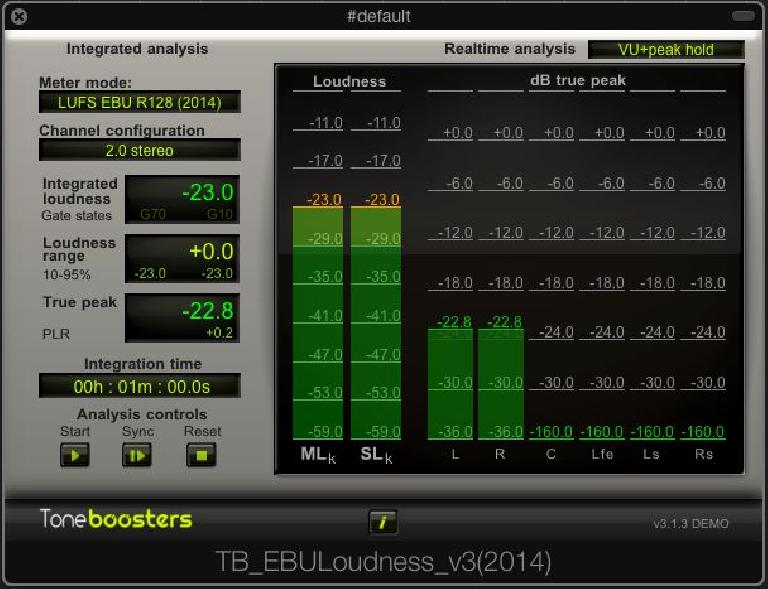

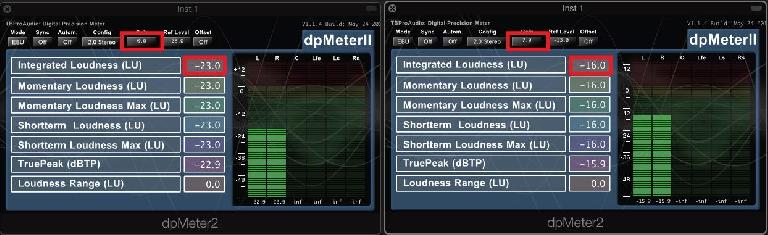

Short Term (2) and Momentary Max (4) (taken over 3s and 400ms respectively) show immediate trends of loudness in your audio and could indicate problematic areas. It’s also good practice to make sure that your highest momentary loudness reading does not go too far past your target level. Loudness Range (LRA) (3), which is measured in Loudness Units (LU) (1 LU increments equal 1 dB increments), is a statistical measure of loudness variation inside your track.

A larger number indicates a wider dynamic range with figures between 6 LU and 12 LU considered good, but 3 - 4 LU is not unrealistic for loop based dance music with a steady beat and only one or two breaks. As mentioned, mixing to peak levels is obsolete. -1dB TP is a technical safety margin, not a target. The Target Loudness (5) on some meters can be set. For mixing, set your target level to -23 LUFS, and for “mastering”, set it to -16 LUFS .

Meters, Presets and Hitting Target Levels

There are plenty of decent (and free) loudness compliant meters (a Google search away), so shifting to LUFS and dB TP measurements is not a financial obstacle. The main difference between free and pro meters is added features and extra configurations, but they all use exactly the same measurement algorithm as defined by the BS-1770 document. Some meters have presets. Use either the BS.1771-3 (usually default) or EBU R 128 modes during mixing. The target level is -23 LUFS by default, leaving ample headroom during mixing, and for normalising to -16 LUFS at the end.

It is not necessary to boost a quiet intro, or lower a loud verse/chorus to “help” the meter, mix and “master” as usual. If, after analysing the whole song, your meter reads -18 LUFS it means you need to turn up the whole track by 2 dB. A few meters have gain functionality built in for this purpose.

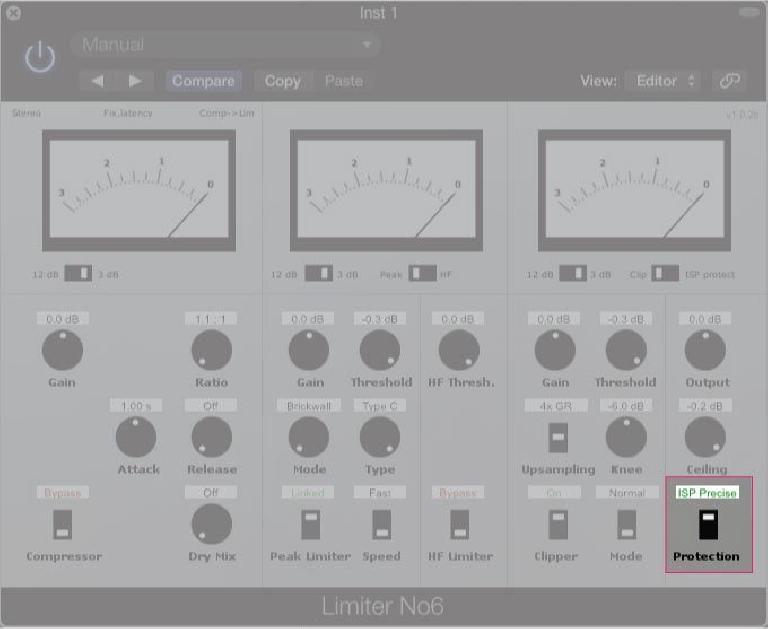

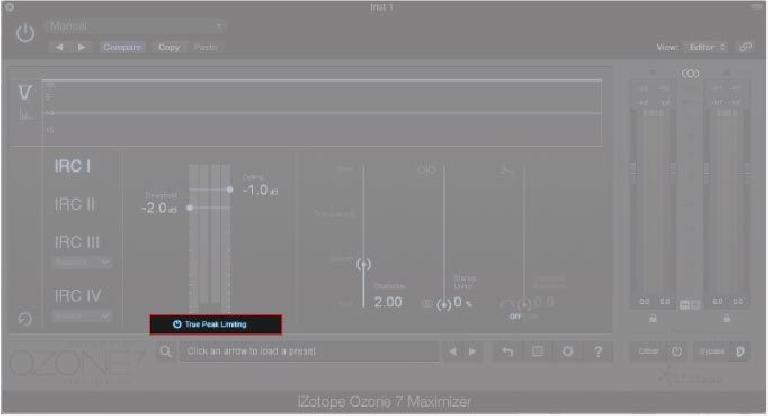

Also, make sure your final limiter can measure intersample peaks (ISP) or has true peak limiting enabled.

Sample Rates and Bit Depths

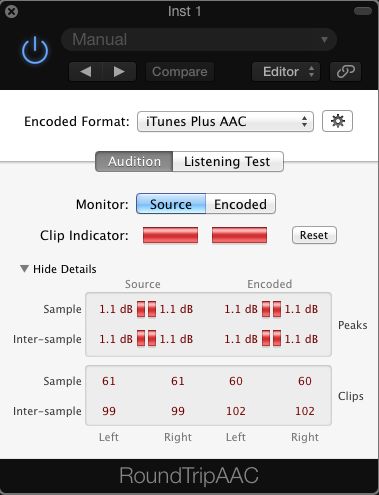

Exporting at 24 Bit/44.1Khz (or higher) is recommended, but if you’re still working at 16 Bit/44.1Khz there is no point to upsampling before finalising, level normalising, and uploading. If you plan to publish on iTunes you should familiarise yourself with their mastering guidelines and the Mastering For iTunes (MFiT) toolkits. The MFiT AURoundTripAAC Audio Unit is a great tool to check for intersample peaks, and to A/B different conversion rates before bouncing.

RoundTripAAC Showing peaks and intersample peaks

Conclusion

Mixing around -23 LUFS and normalising to -16 LUFS/-1dB TP is considered “future proof” for music streaming online. It’s loud enough for mobile devices, optimal for conversion to lossy formats, and tailored for streaming platforms, including services not using loudness standards yet like Bandcamp and Soundcloud.

Anecdote

During preparation for public release of my own productions I personally aim for roughly -16 LUFS/-1 dBTP for Bandcamp, Youtube, and Soundcloud. That said, only a fraction of my current online catalog is loudness normalised.For the commercial work I do for Japan, it depends on the format. For streaming content (Twitch/Youtube) I deliver at -16 LUFS/-1 dB TP, and for terrestrial broadcast I deliver at -23 LUFS/-1dB TP (+/- 0.5 LUFS) as per Japanese loudness regulations.

For short films I usually deliver at -23 LUFS (anchored to dialogue), unless otherwise specified.

How it is handled from that point on is beyond my control.

TL/DR: -16 LUFS/-1 dB TP is widely considered to be an appropriate integrated loudness for music material and is optimum for streaming and mobile devices.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

What about momentary loudness?

I was scratching my head for quite a while when reading about this whole thing about iTunes and -16 LUFS, because whenever I run mostly any modern super popular track out of iTunes and run it through IZ insight or ProL I have a LUFS or RMS level waaaay above -16. Then I realized its because I don't have soundcheck enabled. So I enabled sound check and sure enough the levels dropped much closer to -16 (actually more like -14 in the track I talk about below).

So my first question is, how many iTunes users actually have soundcheck enabled? I listen on a desktop computer. Perhaps maybe on mobile soundcheck is enabled by default?

But beyond that , I am wondering something a little bit more bigger in the philosophy of the loudness war.

I am writing this comment in March 2018. So I'm gonna take Taylor Swift as the example. Her recent single "Look what you made me do" has over 800 million views in 6 months on her youtube vevo channel. I don't care what anyone says, this track is undeniably in the realm of music that people find pleasurable to listen to in 2018. If anyone tries to argue with this, just stop you're wrong. Also, I have no idea who produced, who recorded, who mixed, or who mastered the album, but I think it is safe to say that each one of these individuals must be at the top of their game, and they know what they are doing.

With that disclaimer out of the way, if you play this track in iTunes with soundcheck disabled, Izotope Insight reports a integrated LUFs of -8.5, a short term LUFS as high as -6.0 at times (maybe higher), and the Loudness range at 6.0 LU. I should add that for the most part, the short term LUFs is closer to between -10 and -8 LUFS through the majority of the track

And before anyone STILL has the urge to say "yeah but that track sucks" or "yeah but Taylor Swift sucks", again, you are wrong. But still, okay then, so go find a modern pop artist you like (that is using a production team as high caliber as hers) and run their music through Insight with the sound check disabled. It will probably be at a similar LUFS. Im talking Pop music here people. If you like some listening to some weird stuff or old school stuff COOL YOU'RE SO COOL ooh wow you are better than me! I like weird stuff and old school stuff too but thats not what Im talking about here.

But this is really not my point, I am just trying to dissuade anyone who is thinking about chiming in with some stupid argument about how Taylor Swift isn't relevant music. She is arguably the most relevant music right now, for better or worse.

So after all this analysis, it got me thinking. If we are aiming to male a pop track in 2018, maybe we should aim for these Taylor Swift type levels and ignore all the recommended super low level standards and just make sure that we don't clip and that we have a decent dynamic range? Because basically why wouldn't we just try to make it as loud as possible with out clipping and also make sure it has a suitable dynamic range for the genre. That way, it will totally smack through iTunes when soundcheck is turned off, but if soundcheck gets turned on, then basically it just gets turned down right? If it has a good dynamic range and it doesn't clip, and then it gets turned down by soundcheck, then it would sound just as good as if it were mastered to a lower volume closer to the "recommended" levels.

So yeah, am I missing something here? Disclaimer, I am in no way a mastering engineer, I am simply trying to investigate all this stuff so I have a better understanding. Thanks so Much Shane if you read and reply to this, and thanks so much to anyone else who has any input on this subject

Taylor Swift rules haha!

p.s. Strobe is much louder on the 5 years of Mau5 greatest hits type album than it is on the original album. So even conservative Deadmau5 gave in to the loudness wars!

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!