In any modern recording session, the performers’ Cue Mix—a.k.a. Monitor Mix—is one of the most important aspects of the process. Every note the musicians or vocalists play or sing is affected by what they hear in their headphones—if the mix is poorly balanced, too wet or too dry, or simply uncomfortable, the performance can suffer in subtle ways. And yet, despite the importance of the Cue Mix, very often it’s given short-shrift—in the hustle and bustle of a busy session it’s often the last thing to be set up, sometimes as a hurried afterthought, almost guaranteeing less than the best the performers have to offer. With that in mind, here are a few things to consider to help intrepid engineers give due diligence to this critical aspect of a recording session.

One And All

In the old days, musicians and singers would all gather in the studio together and play—what they heard in the room while tracking was the “cue mix”. But as multitrack recording took over, the need for isolation changed the process—even when playing together, musicians were baffled off or isolated in booths, making them dependent on the mix pumped into their headphones to hear each other properly. And of course the more piecemeal approach of overdubbing tracks one-by-one requires a headphone mix of the previously-recorded parts for the individual performers.

In either case—tracking or overdubbing—the performer(s) rely on the headphone cue mix supplied by the engineer, placing the onus on the control room staff to provide a good mix. There are both technical and creative considerations that come into play when setting it up.

Set-up

As most people know, the headphones used for the performer’s Cue Mix need to be closed-ear—a.k.a. circumaural—designs. These are the kind that completely enclose the ears with a seal that keeps the sound in the phones from leaking out and being picked up by the sensitive, (typically) close-positioned studio mics. It’s important to make sure that the phones selected are really providing a good seal; some phones look like sealed designs but actually permit some sound to escape—this may be done to provide a more open sound quality, but it does make them unsuitable for recording.

Even if the phones chosen are a proper sealed design, there are still potential pitfalls. Some vocalists—especially those less accustomed to recording with phones on—may have some pitch problems with sealed headphones. A singer may be used to subconsciously using the sound of his own voice in his head as a reference to stay on pitch, and if the headphone sounds dominates, a slightly pitchy performance may result. Many singers like to remove one earcup, so they can hear the cue mix but still hear their own voice acoustically. This is fine, as long as the engineer notices it, kills the sound feeding the unused earcup, and pans the entire monitor mix to the other side. If he fails to address it, not only will sound likely leak into the mic from the open earcup, but the singer will hear only half the monitor mix, which—if it’s a stereo mix—might not be the best blend to sing along with.

The headphones used for a Cue Mix don’t necessarily have to be as flat as ones you might choose to employ as a reference for mixing or mastering. Many people enjoy a slightly hyped sound—for years the Sony 7503 has been a popular headphone for monitor mixes, and it has a really bright response. As long as the tonality is reasonably well-balanced, any high-quality, well-isolated phone should be suitable.

The Mix

The Cue Mix itself is, of course, key to the whole thing. It can be tempting—especially for an engineer working alone who’s beset by other issues—to just quickly route a copy of the same monitor mix he’s listening to in the control room out to the performer(s). But this is almost always a bad idea—setting up a dedicated Cue Mix really is a necessity. There are a number of ways this can done in a typical modern DAW-based studio.

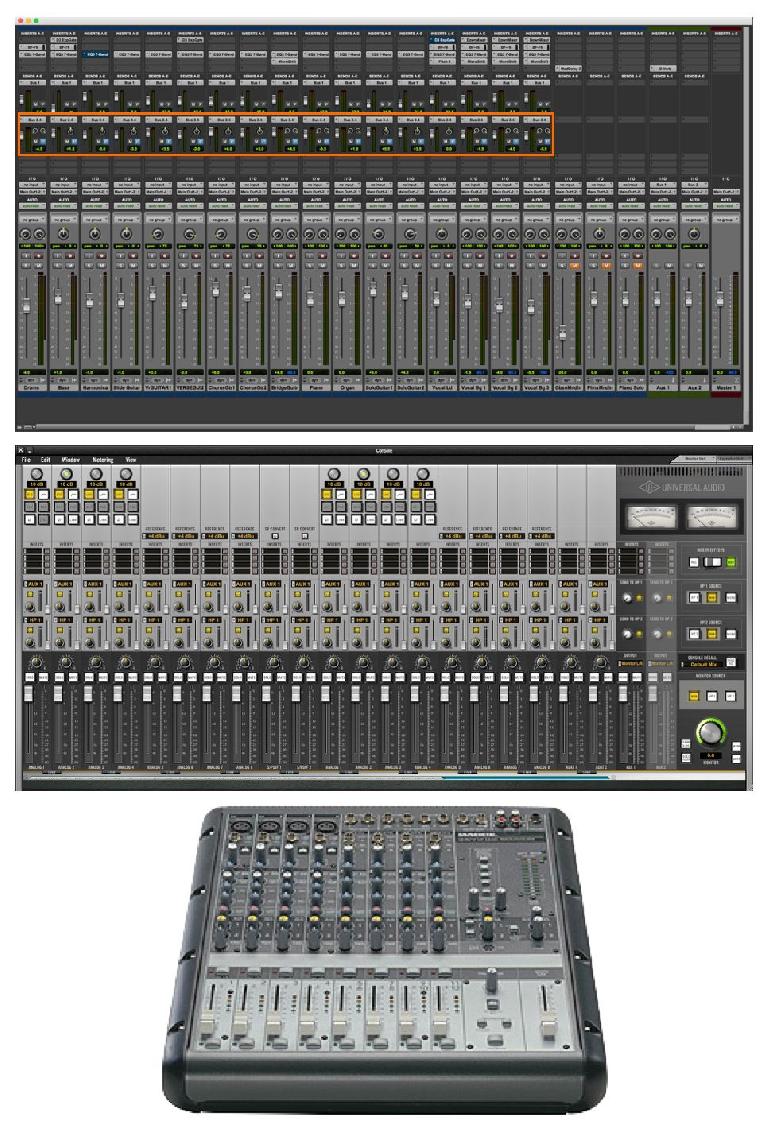

One way would be to use Pre-Fader Sends in the DAW to create one or more independent monitor mixes. Naturally, this will require one or two extra outputs on the interface for each separate (mono or stereo) cue mix, fed into headphone amp(s). But while this is convenient, there may be some drawbacks. If the first engineer is busy, he now has to also deal with setting up the cue mixes—with larger sessions this can distract from other critical recording setup tasks (like level setting and gain-staging). Additionally, Cue Mixes that come from within the DAW will be subject to system-wide Latency (monitoring delay), which may be intolerable for performers, who often can feel even a small lag and be distracted by it to the degree of compromising their timing or feel. If the system can’t be run at a suitably low buffer setting (32, 64, or 128 at most), then a more direct way of setting up the Cue Mix may be needed.

Many interfaces nowadays include internal DSP which provides the option to set up a Cue Mix within the interface itself—besides taking some strain off the computer’s CPU, the practical advantage is that live signals don’t have to pass through the DAW/computer’s i/o RAM buffers, which are the cause of the bulk of the system Latency in any DAW rig. The live audio signals may pass through an AD/DA converter, but that only adds a millisecond or two of Latency at worst (as opposed to 8-12ms or more from the DAW/buffers) before they’re routed back out (again, through extra outputs) to the headphones. Another advantage is that it may be possible to have a second engineer manage the cue mix (setting it up, dealing with performers’ requests), freeing up the first engineer for other tasks.

A third possibility is to set up the Cue Mix(es) in the analog domain—this is a possibility if an analog mixer (even a small one) is available to run the live signal through before they’re sent to the interface/DAW. Once again, these mixes can be easily handled at the analog board by a second engineer, and they’ll provide a true Zero-Latency signal (at least for the live audio). The downside is that the performers won’t be able to hear any DSP processing (either from the DAW or the interface’s onboard DSP), although of course it’d still be possible to add Send & Return effects like Reverb.

But wherever the Cue Mix is created, naturally the mix itself is critical to providing the performers with the best environment to do their thing. With that in mind, here are a few things to think about.

Stereo Or Mono

The Cue Mix doesn’t necessarily have to be a full stereo mix—for the purpose of playing along with, a good mono mix can be just fine. Some performers may even like to hear a mono mix of the track in one ear and their own voice or instrument isolated in the other ear, and if they’re comfortable with this, then there’s no reason not to do it. With larger sessions (multiple musicians), mono Cue Mixes can double the number of independent mixes available. And that brings us to another issue—keeping the customer satisfied.

The Customer Is Always Right...?

The main reason for creating a dedicated Cue Mix (rather than using the CR rough mix) is that different performers will have different needs when it comes to the mix they’re listening to while recording. Some players may prefer to hear only (or primarily) some instruments in the backing track, the better to cue off certain elements (like a bass player who might want to hear mostly kick and snare in the cans). And when it comes to level, again, everyone is different. Most performers want to hear themselves well above the backing track, but I’ve known more than a few who prefer the opposite—their own instrument almost buried in the mix, the better to stay in good time with what’s already recorded.

For the most part there’s no right or wrong when it comes to performers’ preferences—if it draws out the best performance(s) they’re capable of, then it’s all good. But there are situations where the player or singer might not really know what will serve them best, and sometime an experienced engineer/producer may step in and push the Cue Mix in a more appropriate direction—a blend that will work better. This is especially true when dealing with performers who—while talented and professional—may have less recording experience, especially with headphone monitoring.

For example, a performer who has too much of his/her own voice or instrument in the Cue Mix may go slightly off-pitch or drift a little out of time here and there simply because their own signal is overpowering the backing track, and they can’t hear the time/pitch reference they need to match clearly enough at all times. A performer may be used to other musicians drifting in time with them (the natural musical push & pull) at appropriate places in a song, but an already-recorded track naturally will not be so accommodating. It’s the responsibility of the engineer/producer to pick up on this, and tweak the live/track balance until the live performance sits in the track properly—otherwise a lot of time may be wasted doing extra takes and/or editing/processing after-the-fact.

Reverb is another area where this is also a relevant concern, especially with singers. You’ll always want to add a little ambience or reverb to a vocalist’s signal in the Cue Mix—too dry a signal will often yield an uninspired performance, and most singers will request some reverb if it’s not provided. However, some vocalists may ask for so much reverb that it negatively affects their performance (pitch issues, again, or lack of vocal energy if the voice is too heavily ‘verbed). The engineer/producer may want to reduce the reverb in the cans, or possibly change to a less enveloping ambience (maybe more of a subtle room tone), listening for how this affects the performance, and settling on the best compromise between rich reverb and a clean, clear vocal sound.

Producer Tricks

In fact, sometimes a producer may “play with” the Cue Mix creatively, to coax a better performance.

For example, a singer may have enough of their own signal in the Cue Mix that they don’t have to work very hard to dominate the mix, and this may result in a less aggressive, or less energetic performance. It’s a common producer’s trick to very subtly push the track against the voice in the Cue Mix, until it just slightly overpowers the vocal, forcing the singer to put a little more “english” into his/her performance to stay comfortably above the music. If done carefully, this may pull a better, more intense performance out of the vocalist (at least when that quality is musically appropriate).

Wrap Up

And on that note I’m out of room, so I’ll just wrap up with another, final reminder—the Cue Mix is more than just a convenience for the performer(s), it’s an integral part of any recording session, and needs to be given its due, both for the performers’ comfort and the best musical results.

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

© 2024 Ask.Audio

A NonLinear Educating Company

Discussion

Want to join the discussion?

Create an account or login to get started!